Climate change is no longer a distant environmental concern or a debate reserved for scientists and policymakers. It is showing up in state budgets, insurance markets, and local communities with growing intensity. From historic flooding and record breaking wildfires to prolonged heat waves and coastal erosion, the cost of climate related damage is rising faster than most states can manage.

As these pressures mount, a growing number of lawmakers believe the current funding model is broken. That belief is why states push to tax fossil fuel companies to fund climate damage programs instead of relying almost entirely on taxpayers and emergency federal aid. For decades, fossil fuel companies have generated enormous profits while greenhouse gas emissions steadily increased. Meanwhile, states are now paying billions to repair roads, rebuild homes, strengthen coastlines, and protect public health. Many officials argue that this imbalance is no longer sustainable. As states push to tax fossil fuel companies to fund climate damage programs, they are attempting to realign responsibility with impact, ensuring that those who contributed most to the problem help finance the solutions.

When states push to tax fossil fuel companies to fund climate damage programs, they are drawing on a principle that has guided environmental policy for years: those who cause harm should help pay for the cleanup. These policies are not designed as blanket energy taxes. Instead, they typically focus on large oil, gas, and coal producers and base fees on historical emissions or extraction volumes. The intent is to avoid placing immediate financial strain on consumers while still generating meaningful revenue for climate response efforts. Supporters argue that this approach reflects economic reality. Climate disasters already cost states tens of billions of dollars annually, and those costs are projected to increase. Dedicated climate damage programs funded by fossil fuel companies could provide reliable, long term funding for resilience projects, emergency preparedness, and infrastructure upgrades. As more states explore this strategy, the conversation is shifting from whether it is justified to how it can be implemented fairly and effectively.

Table of Contents

States Push to Tax Fossil Fuel Companies to Fund Climate Damage Programs

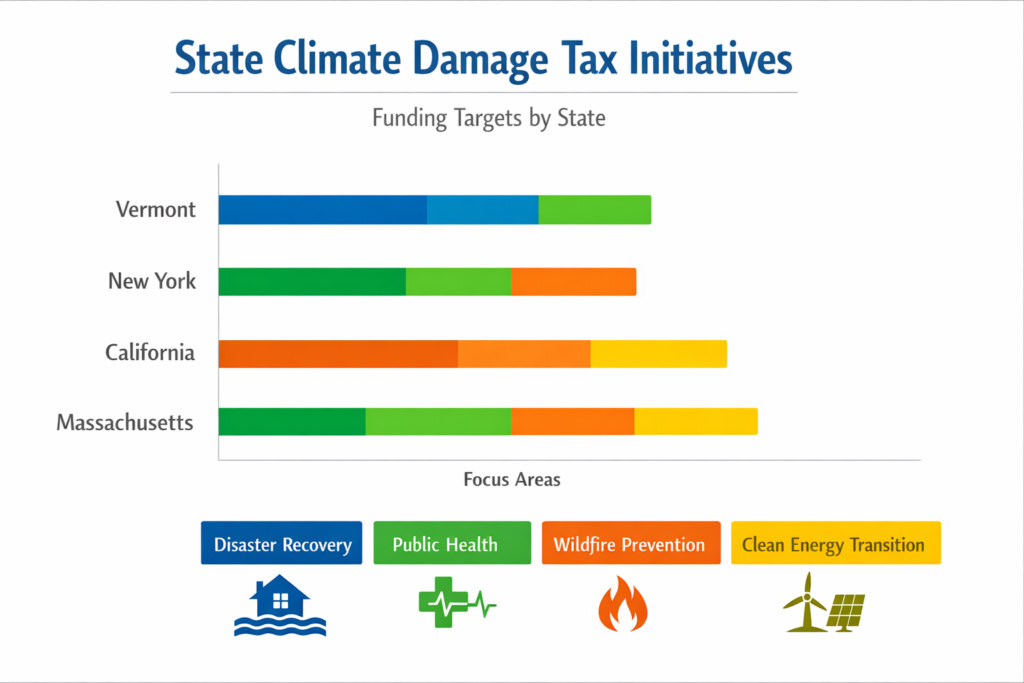

| State | Policy Status | Companies Targeted | Intended Use of Funds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vermont | Enacted | Major fossil fuel producers | Flood recovery and infrastructure repair |

| New York | Proposed | Oil and gas corporations | Climate adaptation and public health |

| California | Proposed | Fossil fuel companies | Wildfire prevention and coastal protection |

| Massachusetts | Under review | Energy producers | Resilience and clean energy transition |

The Rising Cost of Climate Disasters

- Climate disasters are becoming more frequent, more severe, and far more expensive. States are dealing with repeated flooding that washes out highways, storms that overwhelm drainage systems, and wildfires that destroy entire communities. In recent years, climate related damage has accounted for a growing share of state emergency spending, often forcing governments to divert funds from education, transportation, and healthcare.

- Insurance coverage does not fill the gap. In many regions, insurers are raising premiums or withdrawing coverage altogether, leaving states as the payer of last resort. This financial strain is a major reason states push to tax fossil fuel companies to fund climate damage programs. Lawmakers argue that without new funding mechanisms, states will remain trapped in a cycle of disaster response without adequate resources for prevention.

How Climate Damage Taxes Would Work

Climate damage taxes are typically structured as fees rather than traditional sales or income taxes. Most proposals calculate payments based on a company’s share of historical greenhouse gas emissions over a defined period. This approach focuses on the largest contributors rather than small producers or end users. Revenue collected is placed into legally protected climate funds. These funds are earmarked for specific purposes such as flood defenses, wildfire mitigation, resilient infrastructure, and public health programs related to extreme heat and air quality. By isolating the funds, states aim to prevent climate money from being absorbed into general budgets and ensure long term investment rather than short term political spending.

Legal Challenges and Industry Pushback

- The fossil fuel industry has pushed back aggressively against these proposals. Industry groups argue that states are overstepping their authority and attempting to impose retroactive liability for climate change. They warn that such taxes could lead to higher energy costs, reduced investment, and job losses in energy producing regions.

- Legal experts note that similar arguments were made during past environmental and public health cases, including hazardous waste cleanup and tobacco litigation. While climate damage taxes represent new legal territory, courts may look to those precedents when evaluating state authority. The outcome of early lawsuits will likely influence how widely these policies spread across the country.

Political Momentum at the State Level

Political support for climate accountability has grown alongside public awareness of climate impacts. Communities that experience repeated disasters often become strong advocates for new funding solutions. Polling in recent years shows that a majority of voters support requiring fossil fuel companies to contribute to climate recovery, especially when funds are clearly dedicated to disaster prevention and infrastructure protection. This momentum has encouraged lawmakers to introduce bills even in politically divided states. As states push to tax fossil fuel companies to fund climate damage programs, the issue is increasingly framed as a fiscal responsibility measure rather than a purely environmental one. For many legislators, the question is no longer whether action is needed, but how quickly it can be taken.

Potential Economic Impacts

Critics argue that taxing fossil fuel companies could have unintended economic consequences, including higher energy prices or reduced investment in domestic energy production. Supporters counter that climate damage already imposes hidden economic costs through disrupted supply chains, lost productivity, rising insurance premiums, and declining property values. Some economists suggest that predictable climate fees could actually support economic stability by reducing long term disaster costs and encouraging investment in cleaner technologies. By internalizing the cost of climate damage, these policies may help correct market distortions that currently allow environmental harm to go unpriced.

What Comes Next for Climate Damage Programs

- The future of climate damage programs will depend on how early efforts perform. If states successfully collect funds, withstand legal challenges, and demonstrate clear benefits, other states are likely to follow. Federal policymakers are also watching closely, as state level action could influence national climate finance strategies.

- As climate impacts intensify, the debate over who pays for the damage will only grow more urgent. Whether states push to tax fossil fuel companies to fund climate damage programs becomes a nationwide standard or remains a patchwork of state initiatives, it reflects a broader shift in how governments are responding to the financial reality of climate change.

FAQs on Climate Damage Programs

What Is the Purpose of Climate Damage Taxes

These taxes are designed to generate funding for disaster recovery, infrastructure repair, and climate resilience by charging major fossil fuel producers.

Will Consumers Pay More For Energy

Supporters argue the focus on producers and historical emissions limits direct consumer impact, though indirect effects remain debated.

Which States Are Leading This Effort

Several states have passed or proposed legislation, with more expected to introduce similar measures in the coming years.

How Are the Funds Used

Revenue is typically placed into dedicated climate funds supporting resilience projects, emergency preparedness, and long-term adaptation.