Scientists have confirmed that living beings emit light through an extremely faint biological process linked to metabolism, and that this emission rapidly fades at the moment of death. Using advanced photon-detection technology, researchers observed measurable light from animals and plants while alive, offering new insight into the chemical processes that define life itself.

Table of Contents

Scientists Confirm Living Beings Emit Light

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Phenomenon | Ultraweak photon emission from living tissue |

| Visibility | Invisible to the naked eye |

| Change at death | Sharp decline immediately after death |

| Cause | Cellular metabolism and chemical reactions |

A Faint Glow That Separates Life From Death

The idea that living organisms emit light may sound extraordinary, but scientists stress that the phenomenon is firmly grounded in established chemistry and physics. The light involved is not visible in everyday conditions and does not resemble bioluminescence, such as the glow produced by fireflies or certain marine animals.

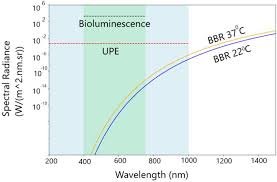

Instead, the emissions are known as ultraweak photon emission, a term used to describe tiny amounts of light released by cells during normal metabolic activity. These photons are so scarce that only highly sensitive instruments, operating in complete darkness, can detect them.

Recent experiments demonstrate that this faint glow is present across a wide range of organisms and diminishes sharply when biological activity stops. Researchers say the findings offer a rare physical marker that distinguishes living tissue from nonliving matter.

What Is Ultraweak Photon Emission?

Ultraweak photon emission, sometimes referred to as biophoton emission, occurs when chemical reactions inside cells release small amounts of energy in the form of light. These reactions are part of everyday metabolism, the complex network of processes that keeps cells functioning.

During metabolic activity, molecules interact, electrons move between energy states, and reactive byproducts form. In rare instances, electrons return from an excited state to a lower energy level and release a photon. This process produces light across ultraviolet and visible wavelengths, though at intensities far below human perception.

Scientists emphasize that this emission is not purposeful or communicative in any known sense. Rather, it is a physical consequence of life’s chemistry.

How Researchers Detected the Light

To study the phenomenon, scientists used highly specialized cameras capable of detecting individual photons. These instruments are far more sensitive than conventional imaging equipment and must operate in carefully controlled environments.

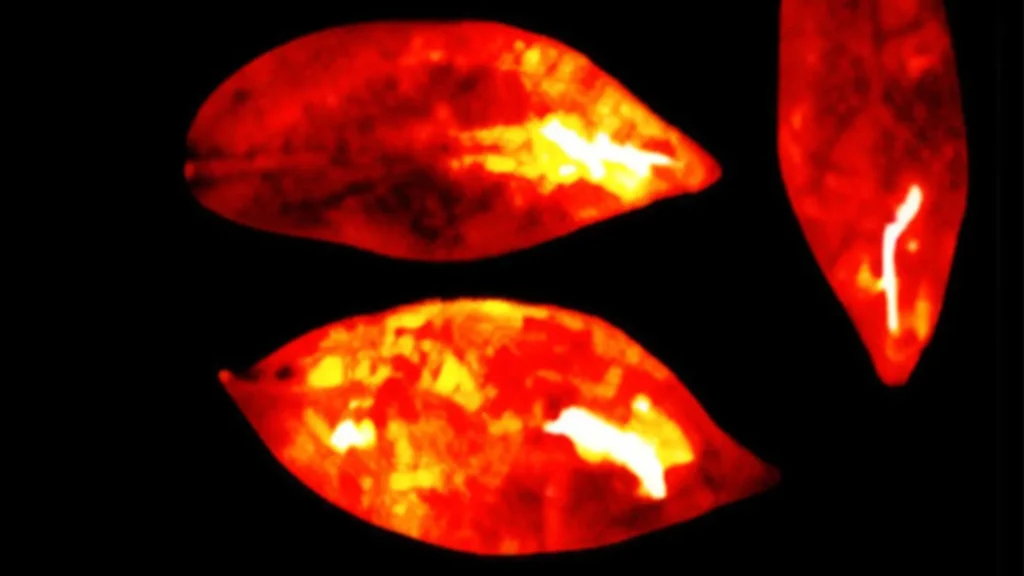

Experiments were conducted in sealed, light-proof chambers to eliminate interference from ambient light. Living mice were placed inside these chambers and imaged over time. Researchers observed consistent photon emission patterns across the animals’ bodies.

After the animals died, imaging continued under identical conditions. The results showed a rapid and substantial reduction in detected light. Similar experiments with plant leaves produced comparable outcomes, with emissions declining after tissues were cut or metabolic processes were halted.

Why the Light Fades at Death

The reason living beings emit light lies in metabolism. As long as cells are alive, they carry out countless chemical reactions every second. Many of these reactions involve oxygen and generate molecules known as reactive oxygen species, which play a role in energy production and cellular signaling.

These reactions occasionally produce electronically excited molecules. When those molecules return to a stable state, they release energy as photons. The process is continuous but extremely inefficient, which explains the faintness of the light.

At death, metabolism stops. Oxygen consumption ceases, chemical reactions slow, and the production of excited molecules rapidly declines. Without these reactions, photon emission fades, leaving behind nonliving tissue that no longer produces light.

How This Differs From Heat or Radiation

Scientists are careful to distinguish ultraweak photon emission from other forms of energy release. The light observed in these studies is not caused by body heat, radioactive decay, or electrical activity.

Thermal radiation occurs in all warm objects, living or not, and follows predictable physical laws. By contrast, biophoton emission occurs only when specific biochemical reactions are active. This distinction allows researchers to isolate metabolic light from background signals.

The difference also explains why the emission declines so sharply at death, rather than gradually fading as tissue cools.

Historical Context: A Long-Studied but Little-Known Phenomenon

Although the findings have recently attracted public attention, ultraweak photon emission is not a new discovery. Scientists have studied similar emissions for decades, particularly in microorganisms and plant cells.

Earlier research was limited by technology. Detecting a few photons per second across a biological surface required equipment that was either unavailable or impractical for large-scale studies. Advances in digital imaging and sensor design have now made such measurements more reliable.

The recent experiments stand out because they captured whole-body emission patterns and directly compared living and dead tissue under controlled conditions.

What the Discovery Does—and Does Not—Mean

Researchers emphasize that the findings should not be misinterpreted. The observed light does not represent a “life force,” consciousness, or energy field in a philosophical or spiritual sense.

There is no evidence that the photons carry information or play an active role in biological communication. Instead, the emission reflects ongoing chemical activity, much like carbon dioxide reflects respiration.

At the same time, scientists say the ability to measure this emission provides a new physical indicator of life at the cellular level.

Potential Scientific and Practical Applications

Although still in the early stages, researchers believe the findings could have practical implications over time.

Medical Research and Diagnostics

Changes in photon emission intensity may reflect oxidative stress, inflammation, or tissue damage. In the future, non-invasive imaging of ultraweak photon emission could help researchers study disease progression or evaluate the effectiveness of treatments.

Agriculture and Plant Science

Plants exhibit changes in photon emission when exposed to drought, injury, or disease. Monitoring these emissions could help farmers detect crop stress earlier than visible symptoms appear.

Environmental and Toxicology Studies

Biophoton emission may offer a sensitive indicator of how organisms respond to environmental pollutants, radiation, or chemical exposure.

Scientists caution that these applications remain speculative and require further validation.

Ethical and Experimental Considerations

Experiments involving animals were conducted under strict ethical guidelines, researchers say. Imaging was non-invasive, and post-mortem measurements were taken only after death had occurred for unrelated experimental reasons.

Scientists also stress that photon emission cannot be used to determine the exact moment of death in clinical settings. The technique requires controlled conditions and cannot replace established medical criteria.

Open Questions Scientists Are Still Exploring

Despite decades of research, many questions remain unanswered. Scientists are investigating whether emission patterns vary significantly between tissues or species, and whether subtle changes correlate with specific diseases.

Another open question is whether biophoton emission is entirely random or reflects deeper organizational principles of metabolism. Current evidence suggests it is a passive byproduct, but research continues.

Why the Findings Matter

At a fundamental level, the discovery underscores a basic truth of biology: life is defined by continuous chemical activity. When that activity stops, the physical signatures it produces—including faint light—disappear.

By revealing a measurable difference between living and dead tissue, the research adds to scientists’ understanding of what life is, not philosophically, but chemically and physically.

Conclusion

The confirmation that living beings emit light that fades at death does not redefine life or challenge existing biology. Instead, it offers a rare glimpse into the subtle physical processes that accompany living systems.

As technology improves, researchers expect these faint signals may help illuminate how cells function, respond to stress, and ultimately fail. For now, the findings stand as a reminder that even the most familiar phenomenon—life itself—still holds measurable secrets.