The claim that England outlawed holiday pastries during the rule of Oliver Cromwell remains one of the most widely repeated seasonal stories. The legend of Mince Pies Under Oliver Cromwell resurfaces every December, but historians say the reality was not a food ban. Instead, it emerged from religious reform, political conflict, and the temporary suppression of Christmas celebrations in 17th-century England.

Table of Contents

Did England Really Ban Mince Pies Under Oliver Cromwell

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| No pastry law existed | Parliament suppressed Christmas observances in 1647 |

| Religious motive | Puritans viewed Christmas as unbiblical |

| Myth formed later | Royalist satire exaggerated reforms |

Today mince pies remain a central element of British Christmas celebrations. Scholars say the endurance of the story reflects how societies interpret major political upheavals through familiar experiences. In this case, a complex religious reform became remembered through the simple image of a missing holiday dessert.

The Mince Pies Under Oliver Cromwell Explained: Christmas Was the Target, Not the Pastry

Historical records show no English statute banned mince pies. Instead, Parliament — influenced by strict Protestants known as Puritans — abolished traditional church festivals.

In 1647, the English Parliament declared Christmas a normal working day. Churches were discouraged from holding special services and businesses were expected to remain open.

Dr. Judith Maltby, a church historian at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, has explained in academic lectures that reformers sought moral discipline in society. “Christmas celebrations had become associated with drunkenness, gambling and social disorder,” she said.

Because mince pies were strongly associated with the holiday feast, they became symbolic of the forbidden celebration. The restriction was cultural and religious rather than culinary.

Civil War Politics and Religious Reform (English Civil War Christmas)

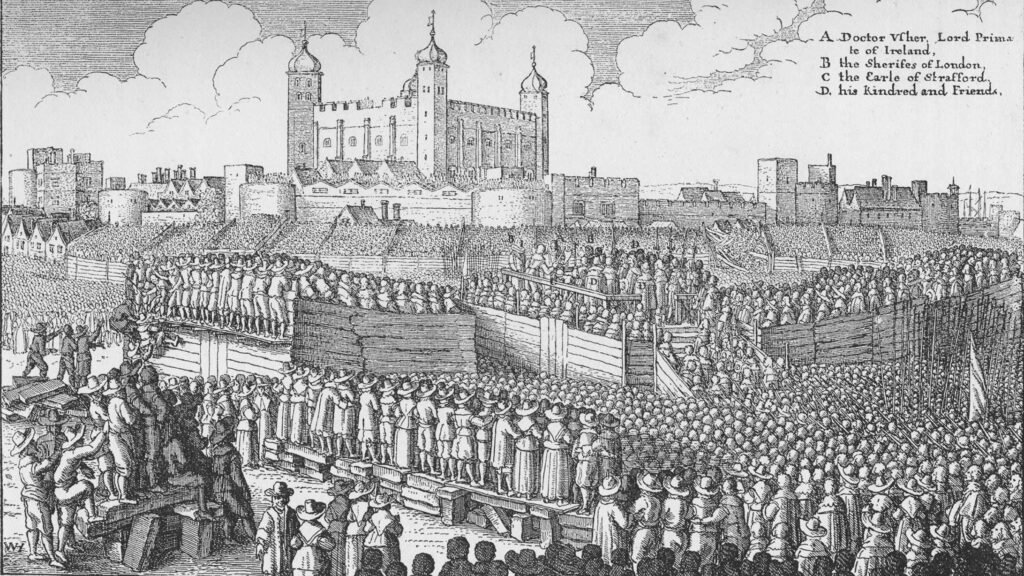

The debate unfolded during the English Civil War (1642–1651), a conflict between Parliament and King Charles I over authority and religious direction.

Puritan leaders wanted to remove customs they believed resembled Catholic practice. Seasonal festivals were among them.

Historian Ronald Hutton of the University of Bristol writes that reformers believed “true religion required simplicity in worship and daily life.” Celebratory holidays appeared spiritually dangerous to them.

Oliver Cromwell, who later became Lord Protector in 1653, supported reformist policies but did not issue a personal food ban. One Christmas in 1644 coincided with a government-ordered fast day. Feasting foods — including rich pies — were discouraged for that single occasion, a detail later magnified into legend.

Public Reaction and Enforcement

Despite official policy, enforcement proved uneven. Many citizens resisted the Puritan Christmas ban.

City records from London and Norwich show shopkeepers closed anyway, and crowds gathered for traditional celebrations. In several towns, riots occurred when authorities attempted to prevent Christmas observances.

Local officials occasionally confiscated decorations or disrupted services, but widespread compliance never fully materialized.

“Ordinary people did not see Christmas as theology,” explained historian Mark Stoyle of the University of Southampton in published research. “They saw it as community.”

The tension demonstrated the gap between government policy and popular custom.

Economic Effects: Bakers, Butchers and Markets

The suppression of Christmas also had economic consequences. Seasonal markets depended heavily on holiday demand.

Bakers who produced festive pies lost business, while butchers saw reduced sales of traditional meats such as goose and beef. Records from municipal guilds indicate complaints about declining winter trade during the 1650s.

Although mince pies themselves were never illegal, the decline in Christmas gatherings temporarily reduced their production. The pastry’s connection to seasonal commerce reinforced public memory that it had been targeted.

How the Mince Pie Myth Began (Puritan Christmas ban)

Royalist writers and pamphleteers opposed Parliament’s reforms and mocked Puritans in political satire. Festive foods became symbolic weapons in propaganda.

The Cromwell Museum notes the claim that mince pies were banned appears in later retellings rather than contemporary law.

Satirical writings described reformers as enemies of joy. Over time, the narrative simplified:

Religious restrictions → suppression of Christmas → memory of lost feast → “ban on mince pies.”

By the 18th century, the simplified version had entered folklore.

The History of Mince Pies

The history of mince pies predates Cromwell by centuries. Medieval versions, known as “coffins” or “chewets,” contained chopped meat, suet, fruits and spices imported through expanding trade routes.

Spices such as cinnamon and cloves were expensive and associated with wealth. Serving the pies demonstrated hospitality and status.

Food historian Annie Gray explains the dish reflected England’s global connections. Imported ingredients came from Asia and the Middle East through European trading networks.

The modern sweet version developed in the 18th and 19th centuries as meat gradually disappeared from recipes.

Why the Pastry Became a Symbol

Cultural historians say food often carries political meaning. During the 17th century, mince pies represented continuity with tradition and monarchy.

To supporters of Parliament, reform meant moral order. To royalists, it meant the loss of English identity.

The pastry therefore became a cultural shorthand. People did not remember a parliamentary ordinance; they remembered a missing holiday meal.

Restoration and Return of Christmas

In 1660, the monarchy was restored under Charles II. Parliament repealed the earlier restrictions and church festivals resumed.

Christmas celebrations returned quickly. Feasts, decorations and religious services resumed openly across England.

The revival reinforced collective memory. The contrast between repression and celebration helped solidify the legend of Mince Pies Under Oliver Cromwell.

Global Legacy of the Story

The myth spread beyond Britain, especially to North America. English settlers carried both Puritan beliefs and Christmas traditions to colonial America.

In fact, some New England colonies later restricted Christmas celebrations as well, reflecting similar religious concerns.

Over time, the story of Cromwell’s supposed pie ban became a simplified explanation of broader religious history, especially in popular media and school textbooks.

Modern Misinformation and Historical Memory

Historians say the persistence of the story illustrates how misinformation develops. Short, memorable claims travel further than nuanced explanations.

Each holiday season, social media posts revive the narrative without context. Museums and scholars regularly publish corrections.

“It’s a powerful example of how cultural memory works,” said historian Hutton in public commentary. “People remember stories, not statutes.”

Historical Significance

The episode highlights tensions between religion, government authority and everyday life. Policies aimed at religious reform affected commerce, culture and social behavior.

Rather than a culinary prohibition, the story represents a society redefining tradition during political upheaval.

The survival of the legend demonstrates how historical narratives simplify complex events into relatable symbols.

FAQs About Did England Really Ban Mince Pies Under Oliver Cromwell

Did Cromwell personally outlaw mince pies?

No. No historical law or decree targeted the pastry itself.

Was Christmas banned?

Parliament suppressed official celebrations in the late 1640s and 1650s.

Why do people believe the story?

Political satire and cultural memory transformed religious policy into a food myth.

Were people punished for celebrating?

Authorities sometimes disrupted gatherings, but enforcement varied widely by region.