The Ancient Alaskan Site in central Alaska is offering new evidence in the long-running debate over how the first people reached North America. Archaeologists studying the 14,000-year-old campsite in the Tanana Valley say it shows clear signs of sustained human settlement during the late Ice Age. The findings help clarify when early populations moved from Asia into the Americas and how they adapted to harsh Arctic conditions before dispersing south.

Researchers from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) say radiocarbon dating confirms human activity at the site around 14,000 years ago. That period falls near the end of the last glacial maximum, when massive ice sheets still covered much of Canada. The discovery adds important context to the broader story of early human migration across Beringia.

“This site gives us a snapshot of daily life in eastern Beringia,” said Dr. Ben Potter, an archaeologist at UAF who has led excavations in the region. “It shows that people were not simply passing through. They were living here, adapting, and raising families.”

Table of Contents

Evidence of Sustained Settlement in Eastern Beringia

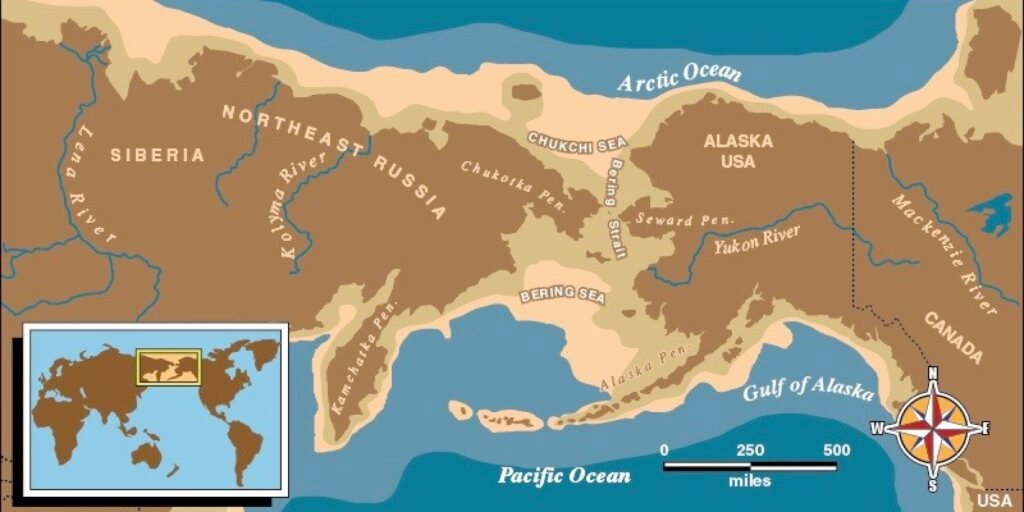

The Ancient Alaskan Site lies in the Tanana Valley, part of what scientists call eastern Beringia. During the Ice Age, lower sea levels exposed a vast land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska. This region supported grasslands, large mammals, and human populations for thousands of years.

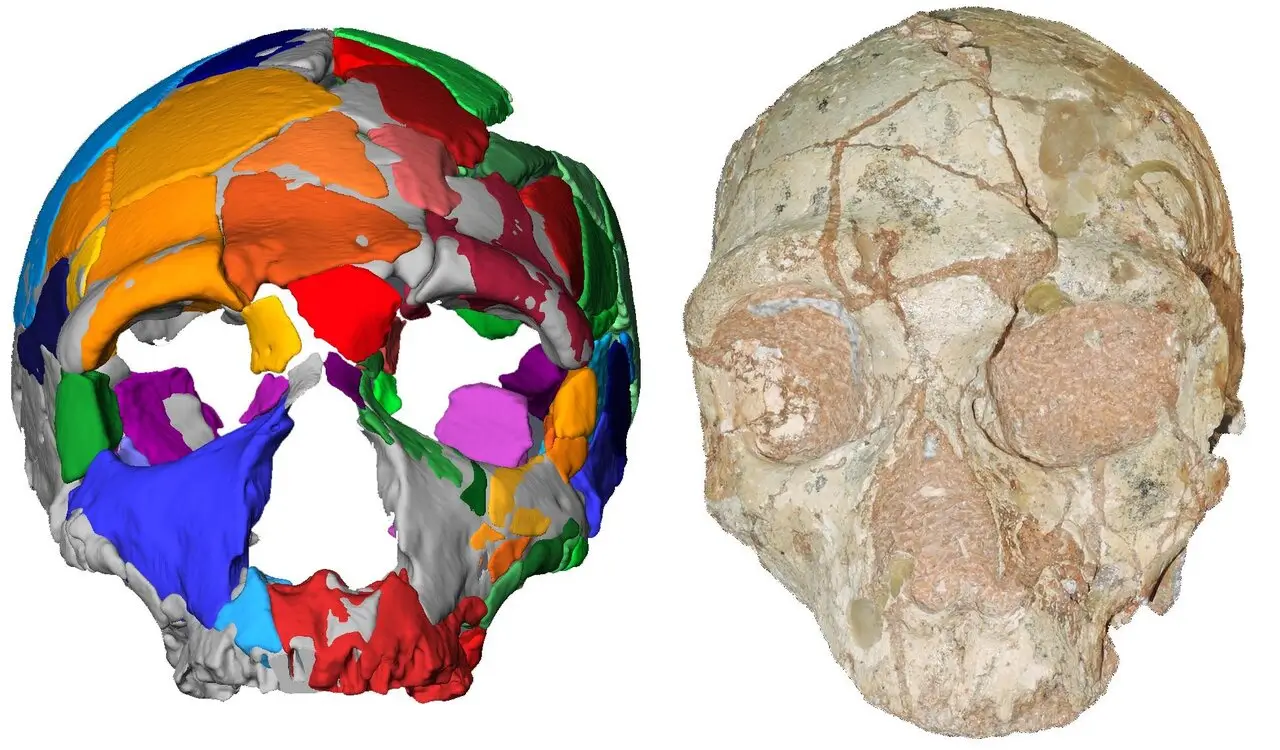

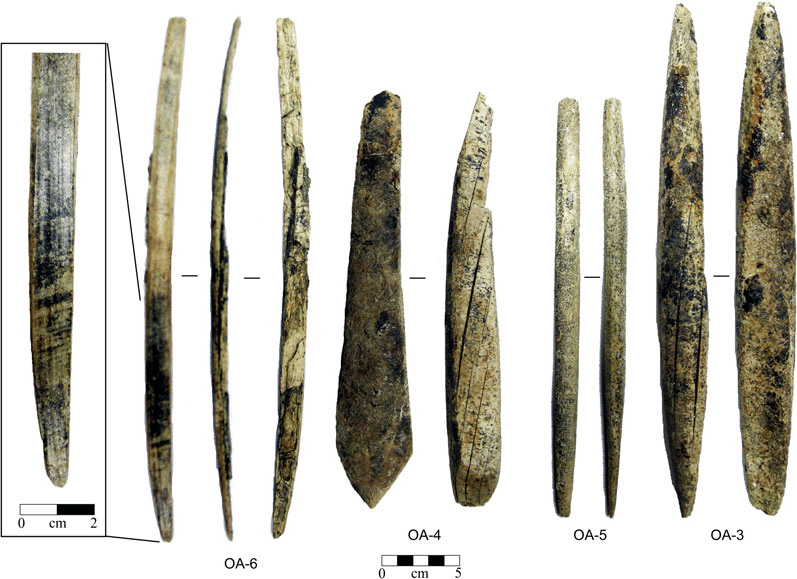

Archaeologists uncovered multiple hearths, stone tools, animal bones, and fragments of worked mammoth ivory. The presence of repeated fire pits and food-processing areas suggests long-term occupation rather than a short hunting stop.

Radiocarbon analysis of charcoal fragments indicates repeated use of the site. According to the research team, the consistency of dates suggests people returned seasonally or maintained semi-permanent settlement patterns.

“This is not a random scatter of artifacts,” Dr. Potter said in a university statement. “We see organized living spaces, structured hearths, and tool production.”

What the Artifacts Reveal About Ice Age Life

The stone tools found at the Ancient Alaskan Site provide insight into Ice Age technology. Researchers identified microblades—small, sharp stone flakes used in composite tools—along with projectile points and cutting implements.

These tools resemble technologies found in Siberia, supporting the theory that early migrants crossed from northeast Asia into Alaska. At the same time, subtle differences suggest local adaptation.

Zooarchaeological analysis shows that inhabitants hunted bison, wapiti, and possibly mammoth. Cut marks on bones indicate systematic butchering. The findings suggest organized hunting strategies and advanced knowledge of Arctic ecosystems.

Researchers also identified plant remains preserved in permafrost soil layers. These botanical traces may offer clues about diet and seasonal patterns. Further laboratory work is underway.

Competing Theories on Human Migration

The Ancient Alaskan Site contributes to ongoing debate about how early humans entered and spread across North America.

The Ice-Free Corridor Hypothesis

For much of the 20th century, archaeologists believed early migrants traveled through an inland passage that opened between two massive ice sheets in present-day Canada. This corridor likely became viable around 13,000 years ago.

However, some geological studies suggest that human presence south of the ice sheets predates the corridor’s full opening. That timing has prompted reconsideration of earlier migration routes.

The Coastal Migration Theory

Another theory proposes that early groups followed the Pacific coastline, possibly using simple boats. Coastal environments may have offered food resources and ice-free pathways earlier than inland routes.

Dr. Potter said the Ancient Alaskan Site does not conclusively favor one model but supports the idea that populations were well-established in Alaska before major southward expansion.

“They were resilient and highly skilled,” he said. “That adaptability could have allowed movement along different pathways.”

Broader Archaeological Context: Pre-Clovis Evidence

For decades, the Clovis culture, dating to around 13,000 years ago, was considered the earliest confirmed human presence in North America. Clovis sites are known for distinctive fluted spear points.

In recent years, however, discoveries at sites in Texas, Oregon, and Chile have produced evidence of earlier human activity. According to published research in peer-reviewed journals, these pre-Clovis sites suggest migration occurred before 13,000 years ago.

The National Park Service (NPS) notes that mounting evidence supports a more complex settlement history involving multiple migration waves.

The Ancient Alaskan Site aligns with this growing body of research. It strengthens the argument that humans occupied parts of North America earlier than previously believed.

Genetic Evidence and the Beringian Standstill

Genetic research also provides context for the findings. Studies of modern Indigenous populations indicate that ancestral groups may have remained isolated in Beringia for thousands of years during the Ice Age. This period, known as the “Beringian standstill,” allowed genetic differentiation before populations moved south.

The Ancient Alaskan Site supports this model by demonstrating sustained habitation in the region during a key climatic period.

Scientists caution, however, that archaeological and genetic timelines must be carefully aligned. “We need more sites with clear dates,” one population geneticist familiar with migration research said. “Each new discovery helps refine the picture.”

Climate Change and Environmental Adaptation

The late Ice Age was marked by dramatic climate fluctuations. Around 14,700 years ago, the planet experienced a rapid warming phase known as the Bølling-Allerød interstadial. Such environmental shifts may have influenced migration patterns.

The Tanana Valley would have offered access to freshwater, game, and raw materials. Researchers believe early settlers strategically chose locations that balanced safety and resource availability.

Permafrost has played a crucial role in preserving the Ancient Alaskan Site. Frozen ground conditions protected organic remains that would otherwise decay. Scientists say continued warming in Arctic regions makes excavation urgent.

Collaboration With Indigenous Communities

Researchers emphasize that archaeological work in Alaska involves consultation with Indigenous communities. Local tribal representatives have participated in discussions about excavation methods and interpretation.

Dr. Potter said collaboration ensures that research respects cultural heritage and integrates Indigenous knowledge systems.

“This history is deeply connected to living communities,” he said. “Scientific study must be conducted responsibly.”

Scientific Significance and Ongoing Research

The research team plans additional excavation seasons to expand the study area. Microscopic analysis of soil samples may reveal plant fibers, pollen, and microfaunal remains. These findings could clarify seasonal occupation patterns.

Isotopic analysis of animal bones may also provide insight into climate conditions at the time of settlement.

Experts say the Ancient Alaskan Site adds a critical data point in a field where well-dated evidence remains limited.

“Archaeology advances one carefully documented site at a time,” said an independent researcher specializing in Ice Age migration. “This is a significant contribution.”

Why the Discovery Matters Globally

Understanding how humans first reached North America helps explain broader patterns of global migration. The settlement of the Americas represents one of the last major human expansions across the planet.

By examining the Ancient Alaskan Site, scientists gain insight into resilience, adaptation, and innovation during extreme environmental conditions. These lessons extend beyond regional history.

The findings also inform modern discussions about climate change. Studying how ancient populations responded to environmental stress offers perspective on human adaptability.

What Comes Next

The Ancient Alaskan Site does not settle all debates about early migration. However, it strengthens evidence that people were firmly established in Alaska before large-scale movement into the continent’s interior.

Further excavation, laboratory analysis, and interdisciplinary collaboration will continue to refine the timeline. Researchers expect that new discoveries in Alaska, Canada, and coastal regions will add detail in the coming years.

For now, the Ancient Alaskan Site stands as one of the clearest examples of sustained Ice Age habitation in eastern Beringia — a crucial chapter in the story of how humans spread across the Western Hemisphere.

FAQ

What is the Ancient Alaskan Site?

It is a 14,000-year-old archaeological site in the Tanana Valley of central Alaska showing evidence of sustained human occupation during the Ice Age.

Why is it important?

It provides strong evidence that humans lived in eastern Beringia earlier than once widely believed, reshaping migration timelines.

Does it prove how people reached North America?

No single site can provide definitive proof. However, it strengthens the argument that early populations were established in Alaska before dispersing south.