Ancient Greek Myths offered early societies an enduring framework for explaining how humanity came into existence and why human life is shaped by hardship, creativity, and moral struggle. Through symbolic narratives involving gods, Titans, and divine punishment, these myths sought to explain not only human origins but also the nature of suffering, progress, and responsibility in a fragile world.

Table of Contents

Ancient Greek Myths as Early Systems of Knowledge

Before philosophy and science emerged as distinct disciplines, Ancient Greek Myths functioned as early explanatory systems, blending cosmology, theology, and ethics. These stories were not designed as historical records. Instead, they addressed fundamental questions: Where did humans come from? Why do we suffer? What separates humans from gods?

Greek myths evolved through oral tradition and later literary works, particularly during the Archaic period between the eighth and sixth centuries BCE. Their enduring power lay in their ability to explain abstract ideas through narrative, making complex concepts accessible to entire communities.

According to Hesiod, one of the earliest recorded mythographers, existence began with Chaos, an undefined void. From Chaos emerged Gaia (Earth), Tartarus (the Underworld), and Eros (desire), forces that shaped the physical and moral structure of the cosmos.

Hesiod’s Theogony provided a genealogical account of the gods, placing humanity within a broader cosmic order rather than at its center.

Humanity’s Place in a God-Dominated Universe

Unlike later traditions that position humans as central to creation, Ancient Greek Myths portrayed humanity as secondary, vulnerable, and dependent on divine will. Humans were neither immortal nor all-powerful. Instead, they existed in a precarious balance between divine favor and divine punishment.

This worldview reflected the lived experience of ancient Greek communities, which faced unpredictable natural disasters, war, famine, and disease. Myths offered explanations for these realities, framing them as consequences of divine decisions rather than random events.

Prometheus and the Shaping of Humanity

The most prominent myth explaining human origins centers on Prometheus, a Titan associated with foresight and cleverness. In several versions of the myth, Prometheus fashioned the first humans from clay or earth, materials that symbolized both humanity’s connection to nature and its inherent fragility.

Ancient sources describe how Athena breathed life into these clay figures, emphasizing that humans possessed intelligence and reason, qualities closely associated with the divine.

This collaboration between Prometheus and Athena reinforced a key theme in Ancient Greek Myths: humans were physically weak but intellectually gifted, capable of creativity yet constrained by mortality.

Fire as the Foundation of Civilization

Prometheus’ defining act was his theft of fire from Zeus. In Ancient Greek Myths, fire symbolized far more than warmth. It represented technology, craftsmanship, agriculture, and the beginning of civilization itself.

Fire allowed humans to cook food, forge tools, build shelters, and organize societies. By granting fire to humanity, Prometheus enabled progress while simultaneously provoking divine wrath.

Zeus punished Prometheus by binding him to a rock, where an eagle consumed his liver daily. The punishment underscored a recurring warning in Greek mythology: progress often comes at a cost, and defying divine authority carries severe consequences.

Pandora and the Origins of Human Suffering

To punish humanity for Prometheus’ defiance, Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora, according to Hesiod’s Works and Days. Crafted by the gods and endowed with beauty and curiosity, Pandora was presented as a gift to humankind.

When Pandora opened a sealed jar, suffering entered the world in the form of illness, toil, and sorrow. Only hope remained inside.

Ancient Greek Myths used this story to explain why human existence is marked by hardship yet sustained by resilience. Scholars note that the myth reflects ancient anxieties about unpredictability and the limits of human control.

The Ages of Humanity: Moral Decline Over Time

Beyond individual creation stories, Ancient Greek Myths also described humanity as progressing through successive eras known as the Ages of Man. Hesiod outlined five ages: Golden, Silver, Bronze, Heroic, and Iron.

The Golden Age depicted humans living in harmony, free from labor and suffering. Each subsequent age marked moral and social decline. By the Iron Age, humanity was plagued by injustice, conflict, and hardship.

Historians interpret this framework as an early attempt to explain societal decay and the loss of perceived moral values, rather than a literal account of human evolution.

Regional Variations in Creation Myths

Ancient Greece was not culturally uniform, and different regions preserved distinct versions of human origin myths. In some traditions, humans were said to emerge directly from the earth, reinforcing the idea of autochthony, or native origin.

Athens, for example, emphasized myths in which its citizens were born from the land itself, strengthening claims of political legitimacy and cultural superiority. These variations demonstrate how Ancient Greek Myths adapted to local identity and social needs.

Philosophical Reinterpretations of Myth

By the fifth century BCE, Greek philosophers began reinterpreting traditional myths. Thinkers such as Plato treated myths as allegories rather than literal explanations.

Plato used mythological narratives to explore ethical and metaphysical questions, including the nature of the soul and the responsibilities of humans within society. This shift marked a transition from myth as explanation to myth as moral and philosophical teaching tool.

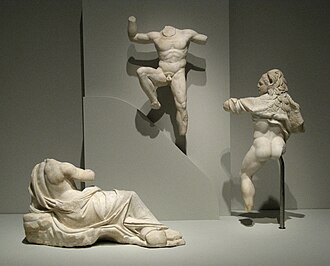

Archaeological and Artistic Evidence

Archaeological findings support the centrality of human origin myths in Greek culture. Vase paintings, temple reliefs, and sculptures frequently depict Prometheus, Pandora, and early humans, suggesting widespread familiarity with these stories.

These artistic representations served an educational function, reinforcing shared beliefs and cultural values in a largely oral society.

Ancient Greek Myths Comparison With Other Ancient Creation Traditions

While Ancient Greek Myths are distinctive, they share similarities with other ancient cultures. Like Mesopotamian and Near Eastern traditions, Greek myths often portray humans as created by divine beings to serve specific purposes.

However, Greek myths uniquely emphasize human intelligence and autonomy, even while highlighting vulnerability and suffering. This balance between potential and limitation remains one of their defining features.

Why These Myths Still Matter

Ancient Greek Myths explaining human origins continue to influence modern literature, psychology, and cultural studies. They offer insight into how early societies understood humanity’s place in the universe and confronted existential uncertainty.

Rather than providing scientific answers, these myths offered meaning. They framed suffering as purposeful, progress as costly, and human life as inherently complex.

Current Scholarly Perspectives

Modern scholars emphasize that Ancient Greek Myths should be understood within their historical context. These stories reflected the realities of ancient life, including environmental instability and social hierarchy.

They also demonstrate early attempts to reconcile human ambition with ethical restraint, themes that remain relevant in contemporary debates about technology and progress.

Final Perspective

While science now explains human origins through evolution, Ancient Greek Myths remain invaluable cultural records. They reveal how early societies used storytelling to understand themselves, their limitations, and their aspirations. In doing so, they continue to offer insight into enduring questions about what it means to be human.

FAQs About Ancient Greek Myths

Were Ancient Greek Myths meant to be taken literally?

Most scholars agree they were symbolic narratives rather than factual accounts.

Why are Prometheus and Pandora central to human origin myths?

They explain both humanity’s creative potential and the origins of suffering.