Macaque Facial Expressions Work Like a Language: and this discovery is flipping the script on what we thought we knew about emotions, communication, and the roots of human speech. For years, scientists believed monkeys’ facial expressions were nothing more than automatic reactions—reflexes tied to internal emotional states. But a new study, published in Science (January 2026), by neuroscientists at Rockefeller University, reveals something far deeper: macaques plan their facial movements, using brain regions responsible for voluntary motor control, similar to how humans manage speech and social interaction. This finding doesn’t just advance our understanding of primates. It reshapes how we view the origin of human language, opens new avenues for medical research, and could even change how artificial intelligence interprets and generates human-like facial responses.

Table of Contents

Macaque Facial Expressions Work Like a Language

The study “Researchers Decode How Macaque Facial Expressions Work Like a Language” takes us one step closer to answering an age-old question: Where does language come from? By showing that macaques plan their facial expressions, using brain circuits tied to voluntary action, this research bridges emotion, intention, and communication. It challenges old-school ideas that separate mind and feeling, logic and expression. Whether you’re working in AI, healthcare, education, or just geeking out on primate science, the implications are clear: communication is older and more intelligent than we thought. And in a way, those monkey faces are speaking volumes—if we know how to listen.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Study Published | Science, January 2026 |

| Lead Researcher | Dr. Winrich Freiwald, Rockefeller University |

| Species Studied | Rhesus Macaques |

| Core Finding | Facial expressions are intentionally produced, not just reactive |

| Brain Regions Activated | Motor cortex, cingulate cortex, premotor cortex, somatosensory cortex |

| Methodology | High-resolution fMRI + electrophysiology |

| Broader Significance | Proto-language communication in primates |

| Official Study Link | Science.org Study DOI |

What Are Macaque Facial Expressions, Really?

Before diving into the neuroscience, let’s set the stage.

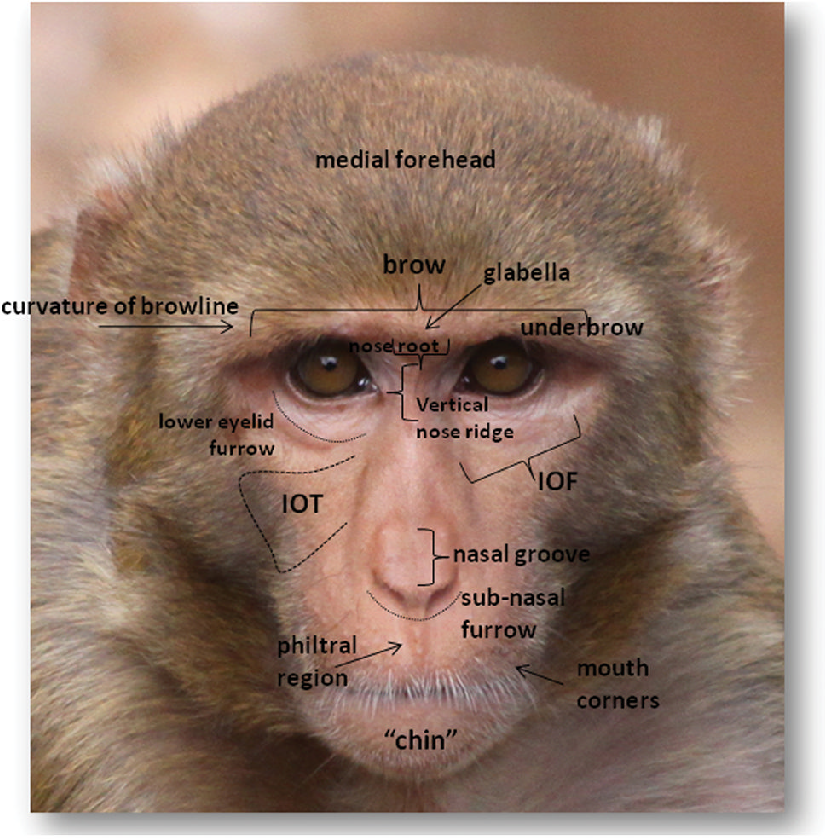

Rhesus macaques are small, social primates found across Asia. Known for their expressive faces, these monkeys grimace, pout, and lip-smack—facial gestures long considered involuntary signals of emotion.

Examples include:

- Grimacing — associated with fear or submission.

- Lip-smacking — often used as a friendly or affiliative signal.

- Cheek puffing or brow lifting — interpreted as curiosity or alertness.

Until now, these expressions were thought to be hardwired emotional responses—triggered by deep, ancient parts of the brain like the amygdala or brainstem. But the new research challenges this by showing high-level planning is involved.

How the Macaque Facial Expressions Work Like a Language Study Was Conducted?

The research team, led by Dr. Winrich Freiwald, designed an experiment that observed macaques during naturalistic face-viewing tasks. The monkeys were shown images and videos of other macaques displaying different expressions. While this happened, the researchers used two tools:

- Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to see which brain regions were active.

- Electrophysiology (using implanted electrodes) to track the precise timing of individual neuron firing.

By comparing expressions like chewing (voluntary) with lip-smacking and grimacing (social and emotional), they discovered something unexpected: the same voluntary motor circuits lit up during all of these expressions.

That means:

- Expressions were not just automatic.

- Macaques’ brains prepared these expressions in advance.

- This suggests intention and cognitive processing.

Some of the specific neural networks activated included:

- Primary Motor Cortex (M1): Controls face and jaw muscles.

- Ventral Premotor Cortex (PMv): Plans movements based on sensory input.

- Cingulate Motor Area (CMA): Involved in decision-making and emotional expression.

- Somatosensory Cortex: Tracks the face’s position and feedback during movement.

Emotion, Communication, and Control: All in One Package

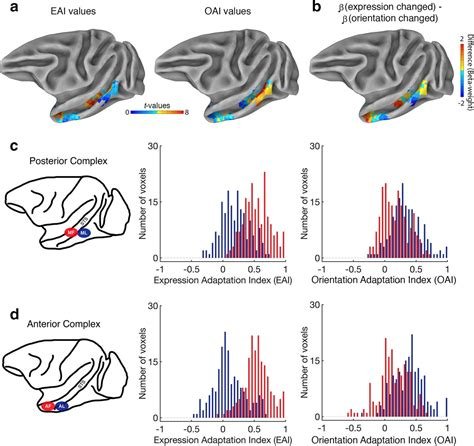

The study revealed two types of brain responses:

- Gesture-General Neurons: Activated before any facial movement.

- Gesture-Specific Neurons: Fired only for particular expressions (e.g., lip-smack vs. grimace).

This pattern of activity was hierarchical, suggesting a top-down control system:

- Emotion is felt or recognized.

- Brain evaluates the social situation.

- A decision is made about which facial expression is most appropriate.

- The motor cortex executes the action.

In other words, the monkey isn’t just feeling—it’s choosing how to show that feeling.

This process echoes how humans make facial expressions—blending emotion, intention, and communication. Think of faking a smile at work or raising an eyebrow sarcastically. It’s not just a reflex; it’s a social tool.

Why This Macaque Facial Expressions Work Like a Language Changes Our Understanding of Communication?

This research isn’t just cool science—it matters for multiple fields:

1. Evolutionary Biology

The study supports the idea that language may have evolved from facial and bodily gestures rather than vocalizations. Before we could talk, we likely signaled with our eyes, mouths, and body postures.

This gives real weight to the theory of “gesture-first” language evolution—suggesting that human language emerged from nonverbal communication systems like those seen in modern-day primates.

“This study fills a crucial gap between reflexive expression and meaningful communication,” said Dr. Michael Platt, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania.

2. Human Psychology and Behavior

It reinforces that human emotions and expressions are deeply social and strategic, not just emotional outbursts. We’re constantly evaluating context, just like macaques do—choosing when to smile, grimace, or frown.

This has important implications for understanding:

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Mood regulation

- Social anxiety

These conditions may not only affect how people feel, but how they plan and interpret facial signals—a process now shown to be more complex than previously believed.

3. AI and Robotics

The findings can help create emotionally intelligent machines. For example:

- Social robots could be designed to mimic human-like facial control.

- AI systems (like customer service bots or caregiving assistants) could respond with intention, not just based on pre-programmed emotional scripts.

Real-World Applications: From Labs to Living Rooms

Let’s break this down with some practical examples:

- A macaque lip-smacks at a lower-ranking monkey. Its brain has already evaluated the situation as safe and friendly—then sends the right signal to maintain social bonds. That’s social awareness.

- A human child smiles at a teacher after being scolded. It’s not joy—it’s a strategic gesture to show submission and avoid conflict. Again, intention.

This opens up new pathways for therapy:

- Stroke recovery: Teaching facial movement by reactivating planning centers in the brain.

- Autism research: Building tools that help users identify and produce intentional facial signals.

- Mental health: Rethinking how expressions reflect emotional health—not as leaks, but as controlled communication.

The Cross-Species Lens: Beyond Just Monkeys

It’s worth wondering: if macaques do this, who else might?

- Dogs show eyebrow raises and tongue flicks in human-facing communication.

- Elephants have nuanced trunk and ear gestures.

- Even birds like crows are showing signs of intentional signaling.

The question becomes: How much of the animal kingdom is using “language-like” signaling? We might be surrounded by unrecognized languages.

Astronomers Detect a Powerful Energy Outburst From a Distant Black Hole

A Simple Lemon and Vinegar Trick May Help Clear Fried Food Smells From Your Kitchen

An Elephant Bone Found in Spain May Be the First Physical Trace of Hannibal