The Race To Restore A Lost Forest Giant Gains Urgent Momentum In New Research as scientists, land managers, and Indigenous fire practitioners intensify efforts to save ancient tree ecosystems threatened by climate-driven wildfires and prolonged drought. Field surveys across western North America now show some of the world’s largest trees are dying faster than they can naturally regenerate, prompting a shift from preservation to active rebuilding.

Table of Contents

A Lost Forest Giant Gains Urgent Momentum In New Research

| Key Fact | Detail / Statistic |

|---|---|

| Tree mortality | Up to 14% of mature giant sequoias lost in recent wildfire years |

| Restoration shift | Seedling planting and controlled burns replacing passive conservation |

| Climate link | Longer fire seasons and extreme heat events increasing wildfire severity |

Researchers say restoration efforts will continue expanding as climate conditions intensify. Whether they succeed may determine not only the survival of iconic trees but also the stability of entire ecosystems that depend on them.

What Scientists Mean by a “Forest Giant”

Ecologists use the term “forest giant” to describe towering, long-lived trees that structure entire ecosystems. The best-known example is the giant sequoia, which can live more than 3,000 years and grow taller than a 25-story building.

These trees are considered keystone organisms. They regulate moisture levels, create cooler microclimates, stabilize soil, and support hundreds of species of birds, mammals, insects, and fungi.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, a single mature giant tree can store tens of tons of carbon dioxide, making old-growth forests central to climate mitigation strategies (KW2).

Why the Crisis Is Accelerating

For centuries, periodic low-intensity fires actually helped these forests survive. Flames cleared brush and opened seed cones, allowing young trees to grow.

Modern fires behave differently.

Climate warming, heavy vegetation buildup, and drought now produce megafires that burn hotter and spread faster. These fires destroy seed sources and damage soil chemistry.

“Historically, fire helped giant trees reproduce,” said fire ecologist Dr. Susan Prichard of the University of Washington. “Today, extreme fire is eliminating the next generation.”

Researchers increasingly link the change to prolonged drought cycles (KW3) and rising temperatures documented across western North America.

Field Evidence From New Research

Monitoring surveys in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains found large areas where mature trees died but seedlings failed to appear. Scientists attribute this to sterilized soil and extreme heat killing seeds before germination.

Dr. Christy Brigham, resource management chief at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, said restoration crews have already planted tens of thousands of seedlings.

“Without intervention, some groves may never recover,” Brigham told park visitors during public briefings.

From Protection to Active Restoration

For decades, conservation policy focused on protecting forests from disturbance. The new research suggests that strategy is no longer enough.

Scientists now recommend active restoration (KW4):

- Prescribed cultural burns

- Selective thinning

- Seed collection and nursery cultivation

- Replanting climate-adapted seedlings

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reports western wildfire seasons now last several months longer than in the 1970s.

That change has forced land managers to treat forests more like infrastructure systems requiring maintenance rather than untouched wilderness.

Indigenous Fire Knowledge Returns

Before modern settlement, many North American forests were regularly managed by Native American communities through seasonal burning. These controlled fires reduced fuel buildup and promoted tree regeneration.

Today federal agencies are partnering with tribes such as the Karuk and Yurok in California to restore those practices.

Researchers say early projects show improved seedling survival and reduced fire intensity.

Fire historians now argue past suppression policies unintentionally increased today’s megafire risks by allowing dense vegetation to accumulate.

The Biodiversity Stakes

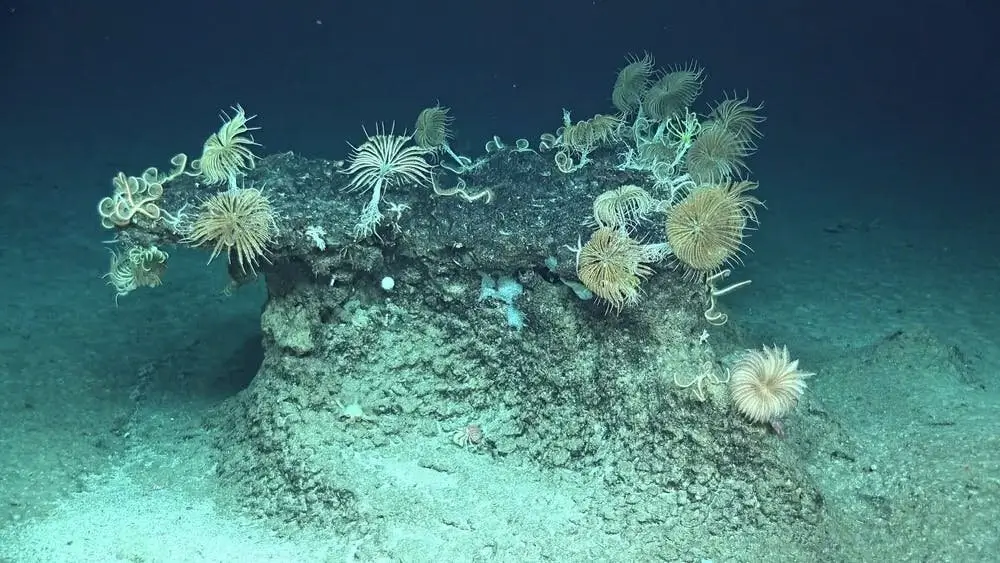

The crisis extends beyond trees. Old-growth forests host highly specialized ecosystems.

Owls nest in hollow trunks. Beetles depend on decaying wood. Fungi networks transfer nutrients between trees underground.

Scientists call this the “wood-wide web,” a fungal communication system that helps forests survive drought and disease.

When large trees vanish, the entire network collapses.

“You don’t just lose a tree,” said a National Park Service ecologist. “You lose a living community.”

Carbon and Climate Implications

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, intact forests absorb billions of tons of carbon dioxide annually.

Large, old trees account for a disproportionate share of that storage. Younger trees grow faster but hold far less carbon.

This means replacing ancient forests with new plantations cannot quickly offset emissions.

Climate scientists warn that widespread loss of old-growth forests would weaken one of Earth’s most important natural climate regulators.

Economic and Water Supply Risks

The issue also affects water security and local economies.

Mountain forests regulate snowmelt and groundwater recharge. After severe fires, erosion increases and reservoirs fill with sediment.

In California, utility companies and municipalities now fund restoration projects to protect drinking water supplies.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates wildfire damage and suppression costs reach tens of billions of dollars annually.

Insurance companies have begun reassessing coverage in fire-prone regions, linking forest health to economic stability.

Global Perspective

The problem is not limited to North America.

Australia’s ancient eucalyptus forests, Europe’s beech forests, and parts of the Amazon rainforest show similar patterns — extreme fires followed by poor regeneration.

International researchers increasingly describe a worldwide transition from stable forests to disturbance-dominated ecosystems.

That shift could reshape biodiversity patterns and regional rainfall cycles.

Policy Debate

Scientists broadly agree restoration is necessary, but debate continues over how much intervention is appropriate.

Some environmental groups worry heavy mechanical thinning could harm habitats. Others argue rapid action is essential to prevent ecosystem collapse.

Federal agencies now emphasize targeted thinning combined with ecological monitoring.

Officials say the goal is not to industrialize forests but to re-establish natural processes disrupted over the past century.

What the Next Decade May Decide

Scientists say the next ten to twenty years will determine whether old-growth forest systems survive intact.

Restoration projects are expanding, but climate projections suggest hotter and drier conditions ahead.

Researchers emphasize that protecting remaining mature trees remains the most effective strategy.

“Once a 2,000-year-old tree is gone, it cannot be replaced in any human lifetime,” one forest restoration scientist said.

FAQs About A Lost Forest Giant Gains Urgent Momentum In New Research

What is being restored?

Ancient canopy tree ecosystems, especially giant sequoia groves and similar old-growth forests.

Why can’t nature fix it alone?

Extreme fires now destroy seeds and soil conditions needed for natural regrowth.

Does planting trees solve climate change?

It helps, but old-growth forests store much more carbon and biodiversity than young forests.

Why are Indigenous burns important?

They recreate historical low-intensity fires that maintained healthy forests for centuries.