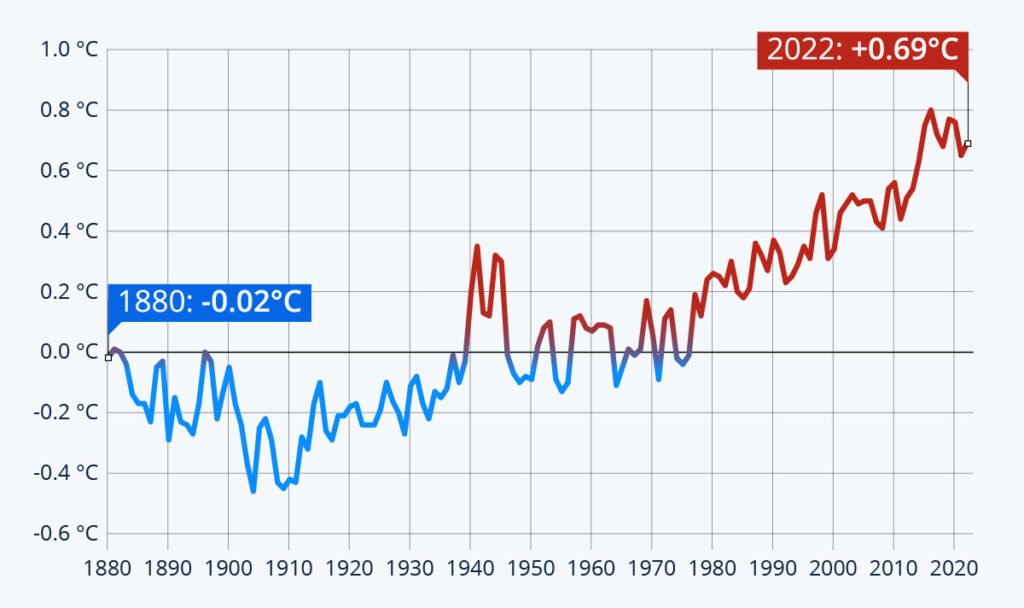

Scientists and economists now say the Climate Change real cost of climate change has been significantly underestimated because traditional economic models ignored damage to the world’s oceans. New research published by marine and climate researchers finds ocean warming, sea-level rise, and ecosystem collapse nearly double the estimated financial harm caused by greenhouse-gas emissions.

Table of Contents

Rising Ocean Damage Is Quietly Doubling

| Key Fact | Detail / Statistic |

|---|---|

| Economic impact | Climate damages per ton of CO₂ nearly doubled |

| Heat absorption | Oceans absorb more than 90% of excess global warming heat |

| Policy implication | Higher damages affect carbon pricing and regulation |

International negotiators are expected to discuss updated economic models in upcoming climate meetings. Scientists say the findings reinforce a broader message: the costs of inaction have been underestimated for decades, and future policies will increasingly reflect the ocean’s central role in the global climate system.

What the Climate Change Real Cost of Climate Change Means

For decades, policymakers relied on a measure called the social cost of carbon, an estimate of economic harm caused by each ton of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. Governments use it to design environmental rules, energy policy, and carbon taxes.

Historically, U.S. and international economic models calculated damages mainly from agriculture losses, heat-related illness, and property destruction from extreme weather. Ocean impacts were largely excluded because they were difficult to quantify in financial terms.

Recent research changes that assumption.

A group of climate economists and ocean scientists concluded that incorporating marine impacts — including coral reef collapse, fisheries decline, and coastal flooding — raises estimated damages dramatically. The revised figures suggest the cost of each ton of carbon emissions is nearly twice previous estimates.

Dr. Christopher Costello, an environmental economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said in a research briefing that “the ocean has been acting as a buffer for climate change, but the economic consequences of that buffering were never counted.”

How Ocean Changes Increase the Real Cost

Heat Stored in the Ocean

The ocean acts as Earth’s primary climate regulator. According to assessments cited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s oceans absorb more than 90% of the extra heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

This stored heat drives marine heatwaves, stronger storms, and persistent weather patterns on land.

Dr. Katherine Richardson, a climate scientist involved in global climate assessments, has explained that ocean warming “locks in climate impacts for decades,” meaning damage continues even if emissions stop immediately.

In practical terms, heat retained in the ocean today can affect weather patterns 20 to 40 years later. That delayed response makes Climate Change uniquely difficult for policymakers because decisions taken now influence economic conditions in future generations.

Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Cities

Warmer water expands, raising sea levels. Melting glaciers and ice sheets accelerate the process.

The United Nations estimates hundreds of millions of people live in low-elevation coastal zones. Even modest sea-level rise increases flood damage, insurance losses, and infrastructure repair costs.

Cities such as Miami, Bangkok, and Jakarta already experience regular tidal flooding. Economists say these repeated losses significantly add to the Climate Change real cost of climate change.

Ports, airports, highways, and water systems were built for 20th-century coastlines. As sea levels rise, engineers must redesign infrastructure, elevating buildings and constructing seawalls. These investments can cost billions of dollars for a single metropolitan region.

Fisheries and Food Security

Ocean warming also reduces fish populations and alters migration patterns. That affects food supplies, especially in countries where seafood provides a major source of protein.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports billions of people depend on marine fisheries for nutrition and income. Declining fish stocks therefore produce economic losses far beyond the fishing industry itself, including jobs, trade, and local economies.

Marine ecosystems are especially sensitive to small temperature changes. Some commercially important species already move toward cooler waters, forcing fishing fleets to travel farther and increasing fuel costs.

Coral Reefs and Natural Storm Barriers

Coral reefs function like natural seawalls. They absorb wave energy and protect coastal settlements from storm surges.

When reefs die from warming and acidification, storm damage increases sharply. Researchers now treat lost reef protection as an economic cost equivalent to destroyed infrastructure.

Dr. Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, a marine biologist who studies reef decline, has said coral ecosystems “provide protective services worth billions of dollars annually,” even though they are rarely priced in markets.

A Brief Timeline of Climate Change Understanding

Scientists have studied Climate Change for more than a century.

- 1896: Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius calculates that carbon dioxide can warm Earth.

- 1950s: Modern measurements confirm rising atmospheric CO₂ concentrations.

- 1988: The IPCC is formed to assess global climate science.

- 2015: Nearly every nation signs the Paris Agreement to limit warming.

However, economic models developed in the 1990s were based largely on land-based impacts. Ocean science was still developing, and many long-term marine effects were unknown.

Today, improved satellites, deep-ocean sensors, and global temperature monitoring allow researchers to connect ocean warming directly to economic losses.

Why Earlier Climate Estimates Were Too Low

Difficult to Price Nature

Economists traditionally measure only direct market impacts — crop losses, property damage, and healthcare costs.

Ocean services, however, are indirect:

- shoreline protection

- carbon storage

- ecosystem stability

- tourism value

Because these services are not bought and sold directly, they were not included in older economic models.

Researchers now call the revised measurement a “blue social cost of carbon,” reflecting the ocean’s role in climate regulation.

Another reason for underestimation was uncertainty. Economic models avoided variables that could not be measured precisely. As scientific understanding improved, economists began quantifying these previously hidden damages.

Human Impact: Communities Already Experiencing Costs

The economic impact is not theoretical. Communities worldwide already face measurable costs.

In coastal Louisiana in the United States, neighborhoods relocate due to persistent flooding. In parts of Southeast Asia, saltwater intrusion contaminates drinking water and farmland. Small island states face the possibility of permanent displacement.

Insurance companies are also adjusting. Some insurers have stopped issuing policies in flood-prone regions because projected losses exceed sustainable coverage levels.

These developments directly reflect the growing financial consequences of Climate Change.

Policy Consequences

Higher estimates of the Climate Change real cost of climate change affect public policy worldwide.

Governments use these calculations to:

- set carbon taxes

- approve or reject fossil-fuel projects

- design environmental regulations

- plan infrastructure investment

According to environmental policy analysts, doubling the economic damage strengthens the case for faster emission reductions and renewable energy deployment.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and similar agencies in Europe and Asia use these estimates when assessing whether a power plant or pipeline project is economically justified.

Economic Debate Among Experts

Not all economists agree on exact figures.

Some analysts argue the new estimates may still be conservative because they exclude biodiversity loss and migration pressures. Others caution that long-term projections involve uncertainty and should not be interpreted as precise monetary forecasts.

Dr. Nicholas Stern, author of a major government-commissioned climate economics review, has previously argued that early estimates underestimated risk because they did not account for irreversible damage.

He noted that climate risks behave more like financial crises than normal economic fluctuations: rare but extremely costly.

Global Equity Concerns

The impacts are uneven. Small island states and densely populated deltas face greater exposure to flooding and fisheries loss.

Countries with lower historical carbon emissions often face higher consequences. Economists say this complicates international climate negotiations and strengthens calls for financial assistance and adaptation funding.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has warned that climate-related losses could overwhelm developing economies without international support.

Looking Ahead

Researchers emphasize the findings do not mean the climate crisis suddenly worsened. Instead, scientists now understand its economic impact more accurately.

As Dr. Costello said during the study announcement, “We are not discovering new damage. We are finally measuring damage that has always existed.”

Future climate assessments will incorporate marine impacts more fully. Policymakers will likely adjust climate regulations and investment planning accordingly.

FAQs About Rising Ocean Damage Is Quietly Doubling

What is the social cost of carbon?

It is an estimate of the economic damage caused by emitting one ton of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Why do oceans affect climate economics?

Oceans influence storms, fisheries, coastal flooding, and ecosystems, all of which have measurable financial consequences.

Does this change climate policy?

Yes. Higher damage estimates can justify stricter emission rules and larger investments in renewable energy and coastal protection.