Scientists have confirmed deep-sea microbial life thriving in highly alkaline ocean environments once believed too extreme to support biology, according to new peer-reviewed research. The discovery, made in sediments far below the Pacific Ocean floor, is prompting researchers to reconsider the environmental limits of life on Earth and beyond.

Table of Contents

A Discovery Beneath the Ocean Floor

The finding emerged from an international research expedition studying sediment cores extracted from the Pacific seafloor near the Mariana Trench, the deepest known part of the world’s oceans. Scientists identified chemical signatures strongly associated with living microorganisms at depths exceeding one kilometer below the seabed.

The environment is marked by extreme alkalinity, with pH levels approaching 12. Such conditions are comparable to household bleach and were long considered incompatible with life.

“This discovery shows that life is far more adaptable than we assumed,” researchers wrote in the study, published in a leading peer-reviewed geoscience journal. The team included microbiologists, geochemists, and oceanographers from several international institutions.

How Life Survives in an Alkaline Ocean

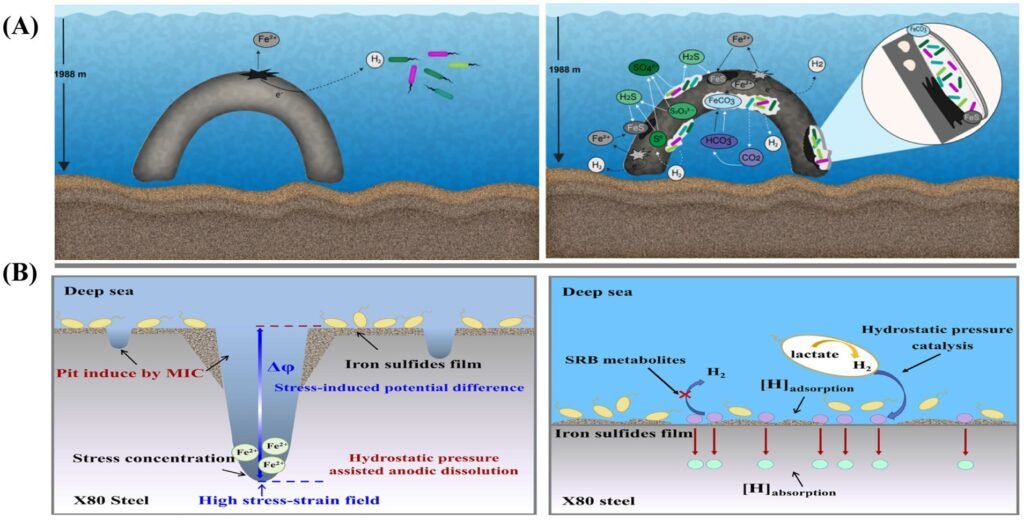

Unlike surface ecosystems, the microbes do not rely on sunlight. Instead, they draw energy from chemical reactions between water and rock, a process known as serpentinization. This reaction produces hydrogen and methane, which microorganisms can metabolize to survive.

Laboratory analysis detected lipid biomarkers—molecular remnants of cell membranes—that scientists widely accept as reliable indicators of living organisms.

According to marine microbiologists involved in the research, the organisms operate at extremely slow metabolic rates, allowing them to persist with minimal energy over geological timescales.

Why the Discovery Matters

The confirmation of deep-sea microbial life in such conditions challenges long-standing assumptions about where life can exist. Until now, most known ecosystems required moderate acidity, accessible nutrients, and relatively stable conditions.

“This fundamentally changes how we think about habitability,” said a senior researcher affiliated with a major oceanographic institute. “If life can persist here, it may exist in places we previously ruled out.”

The findings also offer clues about early Earth, when oceans were chemically different and sunlight-dependent life had not yet evolved.

Implications for Astrobiology

The discovery is drawing significant attention from scientists working in astrobiology, the study of life beyond Earth. Several icy moons in the solar system, including Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus, are believed to harbor subsurface oceans with similar chemistry.

“If these microbes can survive in Earth’s alkaline ocean crust, it strengthens the case that life could exist elsewhere,” noted a planetary scientist not involved in the study.

Scientific Caution and Next Steps

Researchers stress that the findings do not imply complex life forms exist in such environments. The organisms identified are microscopic and represent some of the simplest forms of life known.

Future expeditions aim to directly sample living cells and analyze their genetic material, which could confirm how long these organisms have survived and how they evolved.

For now, the discovery stands as one of the strongest demonstrations yet that life’s boundaries are wider than previously believed.

Concluding Context

As deep-sea exploration technology advances, scientists expect more discoveries from Earth’s most remote environments. Each finding, researchers say, helps refine the search for life both on this planet and beyond.

FAQs About Scientists Confirm Life in an Unexpected Place

What is deep-sea microbial life?

It refers to microscopic organisms living far below the ocean surface, often without sunlight or organic nutrients.

Why is an alkaline ocean significant?

Extreme alkalinity was once thought to prevent biological processes, making the discovery scientifically significant.

Does this mean life exists on other planets?

No direct evidence yet, but the findings expand the types of environments scientists consider potentially habitable.