Scientists have identified living microorganisms inside Fukushima’s Damaged Reactors, discovering active microbial communities in radioactive water beneath the destroyed nuclear units in Japan. The organisms, found more than a decade after the 2011 disaster, appear to be metabolizing and reproducing in an environment once believed sterile. Researchers say the finding could influence nuclear decommissioning efforts and broaden scientific understanding of life in extreme conditions

Table of Contents

Living Organisms Surviving Near Fukushima’s Damaged Reactors

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Discovery | Active microbial life in contaminated reactor water |

| Environment | Highly radioactive flooded chambers |

| Importance | May affect nuclear decommissioning and astrobiology |

Japan’s government says decommissioning Fukushima will likely take 30 to 40 years. Scientists continue to study the microorganisms to determine their long-term effects on reactor materials. Researchers say the discovery inside Fukushima’s Damaged Reactors underscores a broader scientific lesson: life often persists even in environments shaped by catastrophic human technology.

What Scientists Found Inside Fukushima’s Damaged Reactors

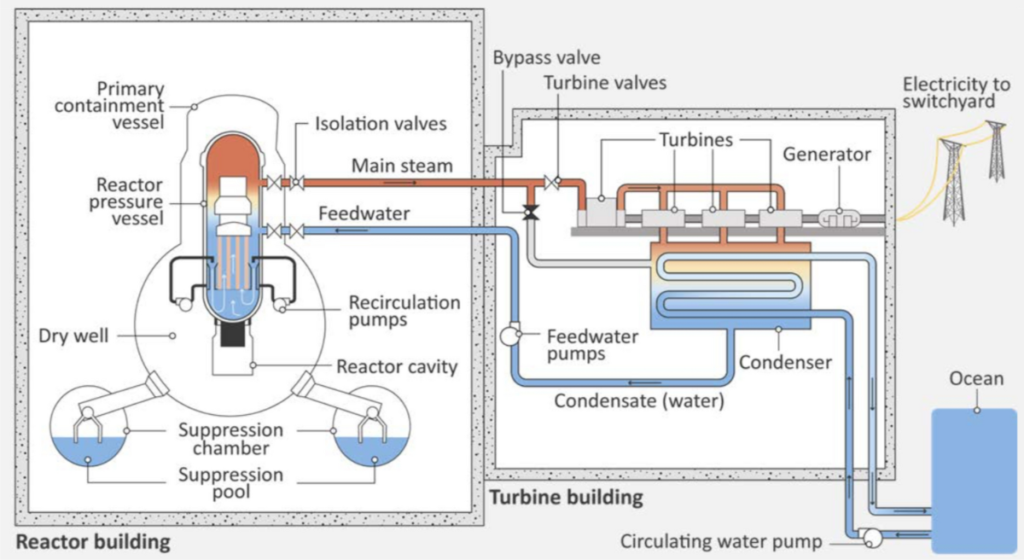

Researchers studying submerged sections of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility collected samples from the torus rooms — containment chambers below the reactor vessels. These areas filled with seawater after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami caused multiple meltdowns.

Laboratory testing revealed dense microbial colonies forming thin biological films along pipes, concrete surfaces, and sediment deposits.

The organisms were not dormant. They showed active metabolism.

“These microorganisms are using chemical energy from metals and minerals,” said environmental microbiologist Dr. Masayuki Kato. “They are functioning ecosystems, not isolated cells.”

Scientists identified marine bacteria species commonly found in ocean environments. Researchers believe the microbes entered the plant with the tsunami water and gradually adapted to radioactive contamination.

Why Survival in Radiation Is Unexpected

Ionizing radiation typically destroys living cells by breaking DNA strands and disrupting protein function. The radiation levels measured near melted fuel debris would normally kill most life forms.

Yet the newly observed communities resemble radiation-resistant bacteria known from extreme environments such as volcanic vents and uranium mines.

What surprised scientists most was the type of organisms present. Instead of rare specialist species alone, researchers found relatively common marine microbes.

Their survival appears to depend on three main biological strategies:

- Biofilm shielding – Microorganisms cluster together in protective layers

- Continuous DNA repair – Cells rapidly fix radiation damage

- Chemical metabolism – Bacteria obtain energy by oxidizing iron and sulfur compounds

“These organisms are essentially eating the environment around them,” said geomicrobiologist Dr. Kenneth Nealson. “Life is using chemistry instead of sunlight.”

Radiation Biology: What the Discovery Means

The finding has drawn attention in the field of radiation biology, which examines how organisms react to radiation exposure.

Previously, scientists believed long-term survival required specialized genes dedicated solely to radiation resistance. The Fukushima organisms suggest a different mechanism: endurance through community behavior and metabolic adaptation.

Researchers now suspect many microorganisms may tolerate radiation better than previously assumed.

“This expands the biological boundary conditions for life,” said astrobiologist Dr. Penelope Boston. “We may have underestimated life’s resilience.”

Implications for Nuclear Decommissioning

Japan plans to dismantle the Fukushima plant over several decades in one of the most complex nuclear decommissioning projects ever attempted.

Microbial activity could affect the process.

Bacteria interacting with steel and concrete may accelerate corrosion of reactor structures and storage tanks. Changes in water chemistry may also influence how radioactive materials move through the facility.

Plant operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) says it is monitoring the biological environment.

“Understanding microbial behavior helps ensure safe dismantling of the reactors,” a company statement said.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has emphasized environmental monitoring as a critical part of long-term containment strategy.

Background: The 2011 Nuclear Disaster

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck northeastern Japan, triggering a massive tsunami. Waves overwhelmed protective seawalls at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station.

Electrical systems failed. Cooling stopped. Three reactor cores melted.

Hydrogen explosions damaged reactor buildings and released radioactive materials into the air and surrounding environment.

More than 150,000 residents evacuated. Many towns near the plant were abandoned for years.

Government estimates place cleanup and compensation costs above $180 billion, making it the most expensive nuclear disaster in history.

Public Health and Environmental Concerns

Despite the microbial discovery, scientists stress the site remains dangerous to humans.

Radiation exposure can increase risks of cancer and long-term illness. Workers at the plant operate under strict time limits and wear protective gear.

Environmental monitoring has detected radioactive contamination in soil and water near the facility, although levels have declined over time due to cleanup efforts and natural decay.

The World Health Organization has previously reported that most public radiation exposure outside the evacuation zone remains low, but monitoring continues.

Comparisons With Chernobyl

Scientists compare the discovery with similar findings at the Chernobyl nuclear site in Ukraine.

After the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, researchers found fungi growing on reactor walls that appeared to use radiation as an energy source — a process called radiosynthesis.

The Fukushima microbes are different. They rely on chemical reactions rather than radiation directly, but both discoveries demonstrate biological adaptation to nuclear environments.

“Chernobyl showed life surviving radiation,” Boston said. “Fukushima shows ecosystems forming in it.”

Importance for Astrobiology Research

The discovery has implications for astrobiology research, the study of life beyond Earth.

Planets and moons without thick atmospheres receive intense radiation from space. Mars, for example, is bombarded by cosmic rays due to its weak magnetic field.

Scientists believe environments beneath the Martian surface could resemble flooded reactor chambers — dark, mineral-rich, and radioactive.

“If microbes live inside Fukushima’s Damaged Reactors, subsurface life on Mars becomes much more plausible,” Boston said.

Space agencies are already studying similar organisms to prepare for future missions.

Future Scientific Studies

Researchers are sequencing microbial DNA to understand survival mechanisms and metabolic pathways. Scientists hope to determine whether microbes can help stabilize nuclear waste or assist environmental cleanup.

Potential applications include:

- bioremediation of contaminated water

- radioactive waste storage stabilization

- industrial corrosion prediction

- deep-space life detection strategies

Scientists caution, however, that research is ongoing and practical applications remain years away.

FAQs About Living Organisms Surviving Near Fukushima’s Damaged Reactors

Are humans safe near these microbes?

No. The organisms tolerate radiation levels dangerous to humans. The discovery does not make the site safe.

Can the microbes remove radiation?

They cannot eliminate radiation, but they may change chemical conditions affecting how radioactive materials move.

Could they help clean nuclear waste?

Possibly. Researchers are investigating whether microbial processes could stabilize or isolate radioactive substances.