Archaeologists exploring Egypt’s submerged city of Thonis-Heracleion have uncovered sunken warships and human burials, offering rare insight into ancient naval power, religious life, and cross-cultural exchange in the Mediterranean more than 2,000 years ago. The discoveries, made beneath the waters of Abu Qir Bay, are reshaping historical understanding of how one of antiquity’s most important port cities functioned before its catastrophic collapse.

Table of Contents

Sunken Warships and Human Burials Discovered

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Location | Abu Qir Bay, Mediterranean Sea, near modern Alexandria |

| Primary Discovery | Sunken warships and human burials |

| Estimated Date | 4th–2nd century BCE |

| Cultural Context | Egyptian–Greek coexistence |

| Cause of Submergence | Earthquakes and soil liquefaction |

A City Lost to the Sea

Thonis-Heracleion was once a thriving gateway between Egypt and the wider Mediterranean world. Located at the western edge of the Nile Delta, the city controlled maritime access to the river’s easternmost channels, making it a critical hub for trade, taxation, and diplomacy.

Ancient texts describe Thonis-Heracleion as the port where foreign ships were required to register and pay customs duties before entering Egypt. Greek merchants, Egyptian priests, sailors, and officials lived side by side, creating a multicultural urban center long before Alexandria rose to prominence.

By the early medieval period, however, the city had vanished from view. It was not destroyed by war or gradual abandonment alone. Instead, a combination of natural forces slowly erased it from the map.

The Catastrophe That Changed Everything

Geological evidence indicates that a series of earthquakes struck the Nile Delta region over several centuries. The underlying soil, rich in water-saturated clay and sand, was especially vulnerable to liquefaction, a process in which solid ground temporarily behaves like liquid.

When this occurred, massive stone buildings lost their structural support. Temples collapsed. Streets sank. Entire districts slid into the sea.

The gradual nature of this destruction explains why many structures, artifacts, and even organic materials were sealed under thick layers of sediment. This natural burial preserved the city in remarkable detail, turning Thonis-Heracleion into one of the most significant underwater archaeological sites ever discovered.

Discovery of the Sunken Warship

Among the most striking discoveries are the remains of a large military vessel, found crushed beneath the collapsed stones of a monumental temple complex. Measuring approximately 25 meters in length, the ship is believed to date to the early Ptolemaic period.

What makes the find exceptional is not only its size but its construction. Analysis of surviving timbers shows a hybrid design, blending Greek shipbuilding techniques—such as mortise-and-tenon joints—with features optimized for Egyptian river navigation, including a wide, flat bottom.

This combination suggests the vessel was designed for both open-sea patrols and movement through the Nile’s shallow channels, reflecting the strategic needs of a port city guarding Egypt’s maritime frontier.

Ancient warships of this type rarely survive, particularly in such a well-documented context. Most wooden naval vessels decayed long ago or were dismantled for reuse. Here, sudden burial under heavy stone blocks shielded the hull from currents, shipworms, and oxygen exposure.

What the Warship Reveals About Power

The presence of a military vessel within the city’s harbor zone indicates that Thonis-Heracleion was not merely a commercial port. It was also a center of state authority and maritime control.

Naval patrols would have monitored foreign ships, deterred piracy, and enforced customs regulations. The warship’s proximity to a major temple suggests close ties between religious institutions and political power, a hallmark of ancient Egyptian governance.

Its destruction, likely caused by the sudden collapse of the temple during seismic activity, offers a frozen moment in time—an unintended record of disaster rather than abandonment.

Human Burials Beneath the Waves

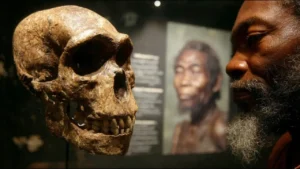

Equally significant is the discovery of human burials in a distinct area of the submerged city. Archaeologists identified graves containing ceramic vessels, food offerings, and personal amulets, many of which align with Egyptian religious practices associated with the afterlife.

Some burial elements, however, reflect Greek customs, including the layout of graves and the style of pottery. This combination supports long-standing theories that Greek settlers maintained their own traditions while participating in local religious life.

The burial grounds appear carefully planned rather than hastily constructed, indicating they were established during the city’s height, not during a period of crisis.

Religion, Identity, and Daily Life

The funerary finds provide rare insight into how people in Thonis-Heracleion understood death, identity, and belonging. Religious objects associated with protection, rebirth, and divine favor suggest deep concern for the afterlife, consistent with Egyptian belief systems.

At the same time, Greek influences reveal a degree of cultural integration unusual for the ancient world. Rather than segregated communities, the evidence points to shared spaces, overlapping rituals, and hybrid identities.

This cultural blending mirrors the city’s economic role as a crossroads of civilizations. Trade goods from across the Mediterranean passed through its docks, and ideas traveled alongside them.

Underwater Archaeology and Scientific Methods

Recovering fragile wooden ships and human remains from the seabed presents extraordinary challenges. Archaeologists rely on advanced underwater techniques, including remote sensing, sediment mapping, and meticulous hand excavation.

Every artifact must be documented in situ before removal. Organic materials are stabilized immediately to prevent deterioration once exposed to air. In some cases, objects remain underwater, preserved where they lie, to protect them from damage.

These methods allow researchers to reconstruct not only individual finds but entire urban landscapes, from harbor installations to residential districts.

Why These Discoveries Matter

The discovery of sunken warships and human burials at Thonis-Heracleion goes beyond spectacle. It fills critical gaps in historical knowledge.

For historians, it offers physical evidence of how naval power supported economic control in ancient Egypt. For archaeologists, it provides a rare case study of an entire city preserved by natural catastrophe. For the public, it humanizes the past, revealing how people lived, worked, worshiped, and died in a place long thought lost forever.

The findings also challenge earlier assumptions that Alexandria replaced Thonis-Heracleion without overlap. Instead, evidence suggests both cities coexisted for generations, serving different but complementary roles.

Broader Implications for Coastal Cities Today

The fate of Thonis-Heracleion resonates strongly in the modern era. Rising sea levels, seismic risks, and fragile coastal geology threaten many cities worldwide.

Studying how ancient urban centers responded—or failed to respond—to environmental change provides valuable long-term perspective. While modern technology offers better tools for mitigation, the underlying risks remain strikingly similar.

What Comes Next

Only a fraction of Thonis-Heracleion has been excavated. Large sections of the city remain buried beneath sediment, awaiting future exploration.

Archaeologists expect further discoveries, including additional vessels, harbor installations, and residential quarters. Each new find has the potential to refine understanding of ancient Mediterranean networks and Egypt’s role within them.

As research continues, the city’s story is gradually resurfacing, piece by piece, from beneath the sea.

FAQs About Sunken Warships and Human Burials Discovered

Q: Why were warships found inside a city harbor?

A: Ancient ports often hosted military vessels to protect trade routes, enforce laws, and defend against piracy.

Q: Are the human burials Egyptian or Greek?

A: Evidence suggests both traditions are present, reflecting a multicultural population.

Q: Why is preservation so good underwater?

A: Rapid burial under sediment limited oxygen exposure, slowing decay.

Q: Is Thonis-Heracleion open to tourism?

A: No. The site is protected and accessible only to licensed research teams.