Cleopatra’s Legendary Pearl Tale: Historians Revisit the Roman Account keeps popping up in classrooms, documentaries, and even casual conversations across the United States. The famous story says Cleopatra once dissolved a priceless pearl in vinegar and drank it just to win a bet with Mark Antony. To a modern reader, that sounds almost like a viral social-media stunt — the ancient world’s version of “watch this.” But history is rarely that simple. When you dig into the sources, you quickly realize the story tells us as much about Roman politics and media manipulation as it does about Cleopatra herself. As someone who has spent years reading classical histories, comparing translations, and reviewing archaeological scholarship, I’ll tell you straight: this pearl tale is one of the earliest examples of how reputation can be shaped — or twisted — by powerful rivals.

After Cleopatra’s death, Rome controlled Egypt, and the Roman Empire needed a clean explanation for why they had gone to war against a foreign queen. That’s where narratives came in. Roman writers crafted a picture of a ruler who was not only wealthy but reckless, someone whose extravagance supposedly threatened Roman values. The pearl story fit perfectly into that messaging campaign.

Table of Contents

Cleopatra’s Legendary Pearl Tale

The Truth Behind Cleopatra’s Legendary Pearl Tale ultimately tells us more about Rome than Egypt. While chemistry shows pearls can dissolve in acid, the historical evidence is weak and politically biased. Roman writers, loyal to Augustus, had strong incentives to depict Cleopatra as extravagant and reckless. Modern historians instead see a capable ruler navigating the world’s greatest superpower. The pearl was likely a symbolic story — a powerful narrative rather than a literal event.

| Topic | Key Information |

|---|---|

| Main Ancient Source | Story recorded by Roman author Pliny the Elder in Natural History |

| Date of Account | Written around 77 AD (over 100 years after Cleopatra’s death) |

| Scientific Plausibility | Pearls (calcium carbonate) dissolve slowly in acetic acid |

| Political Context | Roman propaganda shaped Cleopatra’s image |

| Cleopatra’s Reign | 51–30 BC, last ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt |

| Academic Reference | Classical Roman texts archived by universities |

Cleopatra Beyond the Legend

Cleopatra VII was the final ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, a Greek-origin royal family that had governed Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great. She wasn’t Egyptian by ancestry but adopted Egyptian customs to legitimize her rule. She even presented herself as the goddess Isis in official ceremonies, which was a clever political strategy — not vanity.

Many Americans imagine Cleopatra mainly through movies, but historical records describe something different. Ancient writers rarely said she was the most beautiful woman in the world. Instead, they emphasized her intelligence and charisma. The Greek historian Plutarch noted that her power came from her conversation, education, and presence.

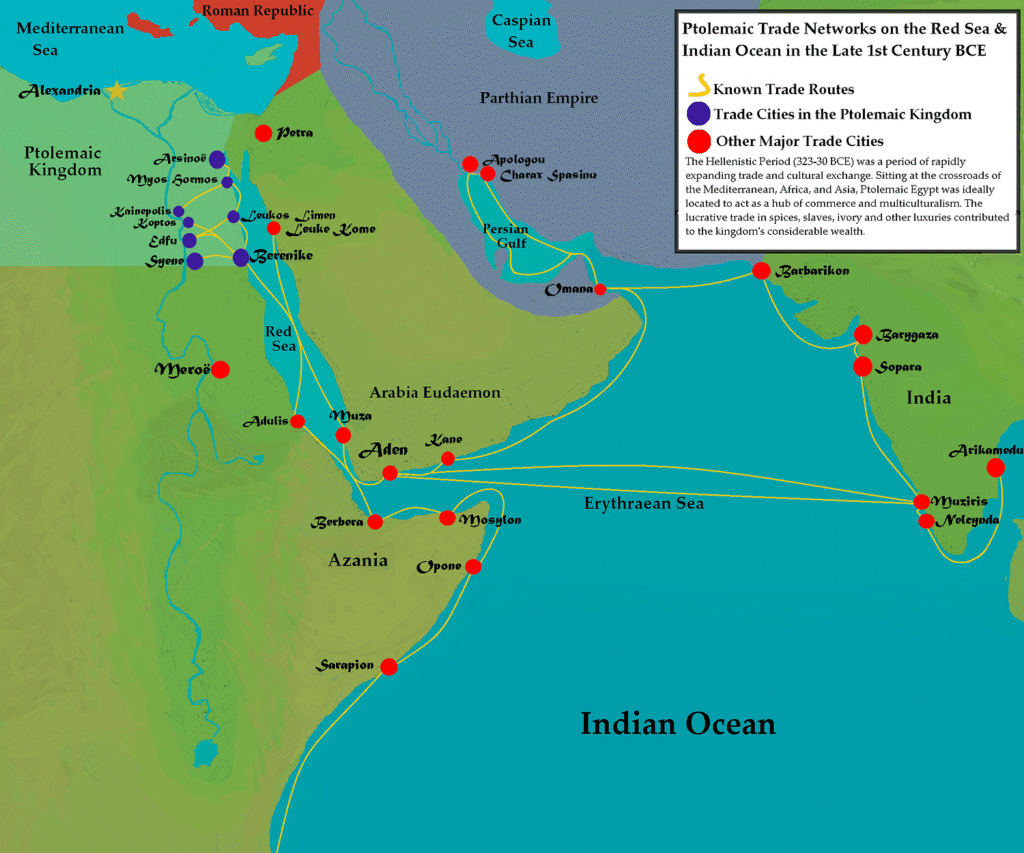

She spoke multiple languages, understood trade routes linking Africa, India, and the Mediterranean, and personally managed diplomatic negotiations. That alone already contradicts the caricature of a careless ruler casually wasting wealth.

The Roman Account of the Banquet

The pearl story comes from Pliny the Elder, a Roman scholar who wrote Natural History, one of the first encyclopedias in Western civilization. He recorded that Cleopatra and Mark Antony had a friendly wager over who could host the most expensive dinner in history.

According to Pliny, Cleopatra removed one of her pearl earrings — supposedly the largest pearls in existence — and dropped it into a cup of vinegar. After it dissolved, she drank the liquid and claimed victory.

Here’s an important detail: Pliny himself admits he relied on earlier reports. He was not an eyewitness. By his own timeline, he was writing more than a century after Cleopatra’s death.

In professional historical analysis, that raises a red flag. When a story passes through generations before being recorded, embellishment is almost guaranteed.

The Science Behind Cleopatra’s Legendary Pearl Tale Claim

Let’s slow down and examine the chemistry carefully.

Pearls are composed mostly of calcium carbonate. Vinegar contains acetic acid. When acid meets calcium carbonate, a reaction occurs that releases carbon dioxide gas — the same bubbling you see when vinegar touches baking soda.

So the reaction is real.

However, controlled experiments show:

- A pearl would take hours to dissolve.

- A large natural pearl could take much longer.

- Ancient vinegar was weak compared to modern solutions.

For Cleopatra to drink it during a single banquet, she would either need extremely strong acid or pre-crushed material. That’s why many historians suspect the story was exaggerated or symbolic rather than literal.

Why Rome Needed This Cleopatra’s Legendary Pearl Tale

After the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium, Augustus became the first Roman emperor. His victory needed justification to the Roman public. Rome traditionally disliked kings and queens; portraying Cleopatra as dangerous made the war seem necessary.

The pearl story achieved three political goals:

- It showed Cleopatra as wasteful.

- It depicted Rome as morally superior.

- It framed the conflict as a defense of Roman values.

Think about it in modern American terms. When governments go to war, messaging matters. Public support depends heavily on how leaders and opponents are portrayed. The Romans understood this perfectly.

Economic Reality: How Rich Was Cleopatra?

Egypt at the time was one of the wealthiest regions in the Mediterranean world. The Nile produced massive grain harvests, and Rome depended on Egyptian wheat to feed its population.

Some economic historians estimate Egypt supplied up to one-third of Rome’s grain imports during certain periods. That gave Cleopatra enormous bargaining power.

Her wealth wasn’t just jewelry and gold. It came from:

- agriculture

- shipping routes

- taxation

- international trade with Arabia and India

So the idea that she would randomly destroy valuable property just to show off actually clashes with her known economic policies. She funded fleets and military campaigns — expenses requiring careful financial management.

Cultural Meaning of Pearls in Antiquity

In Roman society, pearls symbolized ultimate luxury. Only elite aristocrats could afford them. In fact, Roman law at times restricted who could wear certain jewels.

So when Roman writers said Cleopatra drank a pearl, they weren’t just describing a stunt. They were sending a message: she represented excess beyond Roman norms.

To a Roman reader, the story meant, “Here is a ruler so decadent she consumes wealth itself.”

That’s propaganda language.

How Historians Test Ancient Stories?

Professional historians don’t accept ancient texts at face value. They compare evidence.

Here is the typical evaluation process:

Source comparison: Are there multiple independent accounts?

Archaeology: Do artifacts support the claim?

Scientific feasibility: Does physics or chemistry allow it?

Political context: Who benefits from the story?

For Cleopatra’s pearl story:

- Only Roman sources exist.

- No Egyptian confirmation survives.

- Science says possible but unlikely in the described time.

- Rome benefits politically.

The conclusion most scholars reach: the story is likely exaggerated.

Influence on Modern Pop Culture

The legend survived because it’s memorable. Renaissance artists painted dramatic banquet scenes. Victorian writers romanticized it. Hollywood adopted it.

Even today, the story shapes Cleopatra’s image in American media. Instead of a multilingual strategist managing an international economy, she often appears as a glamorous spender.

It’s a reminder that stories stick longer than facts.

Practical Lesson for Readers

This topic isn’t just ancient trivia. It offers a real-world takeaway: always evaluate sources.

When reading historical claims — or even modern news — ask:

- Who wrote it?

- When was it written?

- Who benefited?

Those three questions form the backbone of professional historical analysis and modern media literacy.

Ancient Creatures From 325 million Years Ago Discovered Deep Inside Mammoth Cave

Ancient Alaskan Site May Finally Explain How the First People Reached North America

What Did Ancient Egypt Really Smell Like? Museums Are Recreating the Aroma of the Afterlife