The Therapeutae were a Jewish ascetic community living in Roman-era Egypt whose disciplined, contemplative lifestyle offers one of the earliest known models of monastic life. Known almost entirely from a first-century philosophical account, the group continues to shape modern debates about the origins of religious withdrawal, spiritual discipline, and communal devotion in the ancient world.

Table of Contents

Who Were the Therapeutae

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Time period | Early 1st century CE |

| Location | Near Lake Mareotis, Egypt |

| Primary source | On the Contemplative Life |

Who Were the Therapeutae?

The Therapeutae were an ascetic Jewish group active during the early Roman Empire, most likely between the late first century BCE and the mid-first century CE. They lived on the outskirts of Alexandria, then one of the largest and most intellectually vibrant cities in the Mediterranean.

The group’s name derives from the Greek therapeutaí, a word with layered meanings. It can signify “healers,” “attendants,” or “servants,” and scholars generally agree it refers to spiritual healing rather than medical practice. Members viewed themselves as caretakers of the soul, dedicated to restoring harmony between the human mind and divine reason.

Unlike urban Jewish communities involved in trade, scholarship, or civic life, the Therapeutae intentionally withdrew from society. They sold or abandoned property, renounced wealth, and reorganized their lives around contemplation, scripture, and prayer.

The Historical Setting: Judaism in Roman Egypt

To understand the Therapeutae, historians emphasize the broader Jewish world of Roman Egypt. Alexandria housed one of the largest Jewish populations outside Judea, with deep engagement in Greek philosophy, language, and culture.

This environment produced thinkers who blended Hebrew scripture with Platonic and Stoic ideas. The Therapeutae appear to have emerged from this intellectual climate, combining Jewish law with Hellenistic philosophical ideals such as self-control, simplicity, and the pursuit of wisdom.

“Egyptian Judaism was not isolated or static,” noted one modern historian in an academic survey. “It experimented with forms of religious life that differed sharply from those centered on the Jerusalem Temple.”

The Only Detailed Source: Philo’s Account

Nearly everything known about the Therapeutae comes from On the Contemplative Life, written by Philo of Alexandria, a philosopher who sought to harmonize Jewish theology with Greek philosophy.

Philo describes the Therapeutae as a voluntary association of men and women devoted to spiritual excellence. He portrays them as peaceful, disciplined, and deeply learned, calling their way of life superior to political ambition or material success.

However, historians approach his testimony with caution. Philo admired the Therapeutae and likely presented an idealized version of their practices. No independent contemporary texts describe the group in similar detail, leaving scholars dependent on a single, sympathetic narrator.

Daily Life in a Contemplative Community

Solitary Living During the Week

According to Philo, the Therapeutae spent six days each week in solitude. Each person lived in a modest dwelling containing a small sacred space used for prayer and study. These rooms were not temples but private sanctuaries where scripture and philosophical texts were read and interpreted.

Fasting was common, sometimes extending for multiple days. The goal was not physical deprivation for its own sake but mental clarity. Food was considered a necessity, not a pleasure.

Study, Language, and Interpretation

The Therapeutae read the Hebrew scriptures alongside interpretive writings, often using allegory. Philo suggests they sought hidden meanings beneath the literal text, viewing scripture as a symbolic map of the soul’s ascent toward God.

Greek was likely their primary language, reflecting Alexandria’s dominant culture, though Hebrew scripture remained central. This bilingual intellectual world placed the Therapeutae at the crossroads of Jewish tradition and Greek philosophy.

The Role of Women in the Community

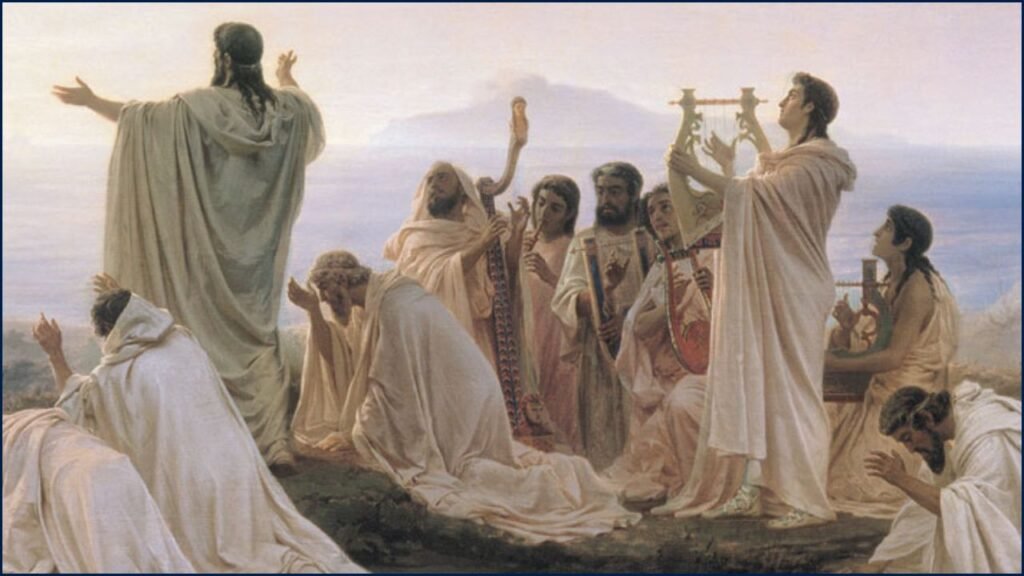

One of the most striking features of the Therapeutae was the full participation of women. Philo explicitly states that women joined the community voluntarily and committed themselves to lifelong chastity and study.

Women attended communal gatherings, listened to teachings, and sang hymns alongside men, though seating arrangements were separated. This degree of religious equality was unusual in the ancient Mediterranean world and has drawn significant scholarly attention.

Sabbath Gatherings and Sacred Time

Once a week, on the Sabbath, the Therapeutae gathered for communal worship. These meetings included readings, sermons by senior members, and choral singing. Meals were simple, consisting of bread, salt, and water.

Every fiftieth day, the group observed a longer festival that combined teaching, hymnody, and an all-night vigil. Scholars note parallels between this cycle and Jewish festival calendars, though adapted to an ascetic setting.

Diet, Clothing, and Material Simplicity

Philo emphasizes that the Therapeutae rejected luxury. Clothing was plain and functional. Diet avoided meat and wine, aligning with broader ascetic ideals of moderation.

“Wealth was seen as a distraction,” wrote one modern scholar, summarizing Philo’s account. “The Therapeutae pursued freedom from desire, not comfort.”

Comparison With Other Ancient Ascetic Groups

Historians often compare the Therapeutae to the Essenes, another Jewish ascetic movement active in Judea. Both groups practiced communal ethics, simplicity, and discipline, but their lifestyles differed.

The Essenes emphasized communal labor and shared property, while the Therapeutae prioritized solitude and intellectual contemplation. The contrast highlights the diversity of Jewish religious expression in the late Second Temple period.

Were the Therapeutae Early Christians?

In the fourth century CE, Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea claimed the Therapeutae were early Christians. Most modern scholars reject this interpretation.

There is no reference to Jesus, baptism, or Christian doctrine in Philo’s account. Instead, the group appears firmly rooted in Jewish scripture and philosophy. However, similarities between the Therapeutae and later Christian monks have fueled debate about indirect influence.

Archaeological Silence and Historical Limits

One of the challenges in studying the Therapeutae is the absence of clear archaeological evidence. No confirmed structures, inscriptions, or artifacts can be definitively linked to the group.

This silence may reflect their modest lifestyle or the limited survival of rural settlements. As a result, historians rely heavily on textual analysis rather than material culture.

Why the Therapeutae Matter Today

The Therapeutae matter because they challenge simple narratives about the origins of monasticism. They demonstrate that disciplined, communal withdrawal from society existed within Judaism before Christianity institutionalized monastic life.

Their example also reveals the fluid exchange of ideas in the ancient Mediterranean, where Jewish tradition, Greek philosophy, and local customs intersected in unexpected ways.

“The Therapeutae remind us that religious innovation often occurs on the margins,” wrote one historian of ancient religion. “They were not mainstream, but their ideas endured.”

What Remains Unknown

Much about the Therapeutae remains uncertain. Scholars debate how large the community was, how long it lasted, and whether similar groups existed elsewhere.

Without new sources, many questions will remain unanswered. Yet their story continues to inform modern discussions about spirituality, withdrawal, and the search for meaning beyond material life.

FAQs About Who Were the Therapeutae

Did the Therapeutae live permanently alone?

No. They lived in solitude during the week but gathered regularly for communal worship.

Were they monks?

They were not monks in the later Christian sense, but their lifestyle closely resembled monastic practice.

Why are sources so limited?

Only one detailed ancient account survives, leaving little opportunity for cross-verification.